Offensive names dot the American street map − a new app provides a way to track them

- Written by Derek H. Alderman, Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

Clear County, Colo., had three roads using the word 'sq—' until May 2024, when officials renamed them.Tom Hellauer/Denver Gazette

Clear County, Colo., had three roads using the word 'sq—' until May 2024, when officials renamed them.Tom Hellauer/Denver GazetteThe racially motivated tragedy in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, when a white supremacist murdered nine Black worshippers, and the deadly white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, two years later compelled Americans to confront the role played by memorials, monuments and other symbols in glorifying racist ideologies.

George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a white Minneapolis police officer in 2020 only lent urgency to that challenge.

Part of the racial reckoning in the wake of Floyd’s death is a movement to remove offensive names from public places. Some names perpetuate demeaning slurs and stereotypes against people of color. Others honor historical figures linked to racism and colonization. This movement is what we geographers call America’s “renaming moment.”

Government officials, activists and other people have called for a renaming of certain places and institutions. Examples include removing Christopher Columbus’ name from a Chicago public school and erasing the name of former KKK leader and governor Bibb Graves from a University of Alabama building. The elimination of names of Confederate generals from several U.S. military bases provides another example.

These changes have become flash points of community activism and debate, both in support of and in resistance to name revisions.

A widespread element in this renaming moment are offensive street names. We believe discussions and decisions about removing these names may benefit from comprehensive sources of information that allow the public to know how pervasive a problem the country might be confronting.

The recent release of an app developed by STNAMES LAB, an international team of scholars of place names, allows users to conduct nationwide inventories of discriminatory roadway names, revealing how often and where they are found.

We believe the app is an important educational tool. It will help communities understand how discriminatory beliefs are woven into everyday spaces and the harm caused by offensive names.

After tracking a few of America’s most contested place and institution names, we believe the app will help people see the changes necessary to recognize and repair past wrongs in street naming.

Recognizing that names can harm and heal

There is growing public recognition that place names are not neutral identifiers of locations. Rather, place names can transmit harmful messages that misrepresent the history and identity of minority communities. As a result, they work against the possibility of a more equal society.

One highly publicized effort at identifying and replacing offensive place names happened in November 2021.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold that post, ordered the removal of the word “squaw,” hereafter called “sq—,” from the names of 650 mountains, rivers and other sites on federal lands. Haaland’s order capped many years of demands from Native American groups to eradicate the racist and sexist label.

Then, in 2022, Haaland established the Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names, comprising members from tribal nations, Native Hawaiian organizations and scholars. Its guiding principles call on the U.S. to recognize the historical role of racism and sexism in naming places. They also highlight how those in power have used names to disrespect, misrepresent and control certain groups that have been historically discriminated against.

Drawing from public comments over two years, the committee found that derogatory place names are a source of recurring trauma for groups that have been historically discriminated against. As one Native American community leader told the committee, “Names matter, as they can build or break a relationship with the land and have the power to uplift or marginalize communities.”

Similarly, a 2022 report by the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers and the Wilderness Society found derogatory place names can create an unwelcoming environment that some people avoid. Additionally, a 2022 study by Emory University found that homes on streets named for pro-slavery Confederate figures sell for less and take longer to sell than comparable houses on nearby roads.

Renaming roads serves as an important moment of community reconciliation. That’s because the frequent use of offensive street names exacts a hefty social and psychological toll on marginalized communities, according to the cultural historian Deirdre Mask.

When hurtful names are removed from roads, some members of oppressed communities describe how the spirit or feeling of places can change and allow healing to begin.

The difference an audit makes

The Interior Department committee suggests that efforts to change offensive names should be driven by research. It encourages local residents to identify where derogatory place names exist, when and how they were named, and how those names can harm the well-being of community members.

Data scientist Catherine D’Ignazio and her team at the Data + Feminism Lab agree. They call for conducting audits that collect and visualize data on unjust names, to challenge the damaging effects and abuses of power behind these symbols.

The newly released street names app from STNAMES LAB allows people to do that. Fed with Open Street Map data, it lets users carry out queries, as well as map and download streets containing certain terms.

Once users enter a name, they can check the specific location of named roads on a map. They can also download query results as a spreadsheet to get the full list of streets.

The app offers an easy visualization of the frequency and geographic distribution of names. You can see whether the name is found across the nation or concentrated in a specific region.

Demonstrating the app

To illustrate the app’s capabilities, we searched for names that have sparked public controversy.

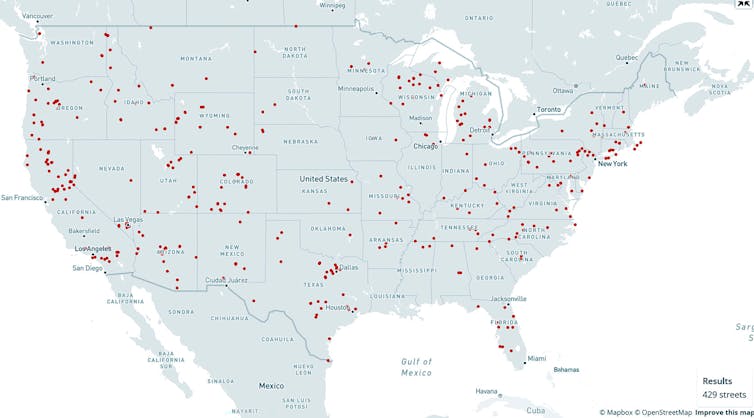

Federal condemnation of “sq—” as a place name does not mean that local authorities will follow suit, even if some cities and states are already doing so. We found 429 streets scattered across 47 states with a name containing the word “sq—.”

Although “sq—” originated in the Algonquian language, European settlers corrupted and misused the word in reducing Native American women to a simplistic and sexualized image. Being called “sq—” is still a painful daily reality for Indigenous women. Many of them say the term injures their self-image and sense of belonging.

Map of U.S. roads named ‘sq—’ from the street names app.https://en.stnameslab.com/the-project/

Map of U.S. roads named ‘sq—’ from the street names app.https://en.stnameslab.com/the-project/The street name app exposes other racist Native American stereotypes. Variations of “redman/men” and “redskin” appear on 211 roads.

“Redskin” is a portrayal of Native Americans as warlike and dangerous. According to Native writer Angelina Newsome, colonialists often used it interchangeably with “savage.”

We found 415 roads in 46 states using the word “savage” in their name.

Though references to “redman” and “redskin” have long shown up in consumer products and sports team mascots, many Native groups challenge these stereotypes as demeaning.

Map of roads named ‘redman,’ ‘redmen’ or ‘redskin’ from the street names app.https://en.stnameslab.com/the-project/

Map of roads named ‘redman,’ ‘redmen’ or ‘redskin’ from the street names app.https://en.stnameslab.com/the-project/Searching for offensive street names across the country is about more than simply collecting information. Data and maps can be part of the process of expanding one’s sphere of awareness and caring for people living with unjust naming practices.

Tracking and visualizing these inequalities is key to developing the “civic imagination” that scholar Catherine D'Ignazio believes is necessary to imagine and call for more inclusive alternatives to the current American landscape of names.

What is at stake is not just removing insulting names in and of themselves, but ensuring that the places marked by these names feel more welcoming and respectful of all Americans.

Derek H. Alderman is affiliated with the Federal Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names, U.S. Department of Interior.

Daniel Oto-Peralías receives funding from the Andalusian Government and ERDF (European Commission) through I+D+i project P20_00808 and UPO-1380998.

Joshua F.J. Inwood does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Derek H. Alderman, Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee