Why Melbourne needs its own version of the Greater Sydney Commission

- Written by Marcus Luigi Spiller, Associate Professor (Urban Planning) - honorary , University of Melbourne

Melbourne’s global reputation for liveability does not resonate with many Melburnians. Its economy has slipped into per capita recession a couple of times over the past decade. Population growth has outpaced the provision of parkland and social housing. Many households must look to fringe areas to find housing they can afford.

Read more: Our cities need city-scale government – here's what it should look like

The Victorian government has duly ramped up its urban management program. New suburbs are well planned if belatedly equipped with the infrastructure they need. A multi-billion-dollar “big build” includes the Metro Tunnel, the West Gate Tunnel, level-crossing removals and, prospectively, a new suburban freeway – the North East Link.

Ordinary citizens may well give the government credit for this ambitious agenda. Equally, they might wonder how all these projects add up to a long-term vision for Melbourne.

The official metropolitan strategy, Plan Melbourne, has little profile in the community. The government gazumped its own plan with its breathtaking 2018 election announcement of a suburban rail loop to reshape the city.

In contrast, the Greater Sydney Commission has devised a compelling metropolitan strategy. Its “three-city vision” has captured the popular imagination and galvanised a degree of infrastructure co-ordination across government agencies and local councils in Sydney.

Read more: How close is Sydney to the vision of creating three 30-minute cities?

Why is Victoria different?

The Victorian government took over the planning of metropolitan Melbourne in 1985. The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) had for three decades managed the city’s development “under licence” from the state. State and local governments jointly “owned” the board as its governing body included state appointees and council-elected delegates.

The MMBW prepared the metropolitan strategy for sign-off by the state, acted as development approval authority for projects of metropolitan significance and delivered key infrastructure. This included water-cycle management, metropolitan parks and, for a time, city-shaping roads. Having its own rates base gave the MMBW a high degree of fiscal autonomy.

Read more: Our legacy of liveable cities won't last without a visionary response to growth

The Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works undertook citywide planning with public input.

State Library of Victoria

The Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works undertook citywide planning with public input.

State Library of Victoria

Bringing metropolitan planning under direct ministerial control seemed like a good idea at the time. The Cain Labor government had come to power with a detailed urban agenda. It included revitalising the CBD, reframing the city around the Yarra, boosting the economy and amenity of the western suburbs and reining in sprawl.

The government did not want a powerful, semi-autonomous, planning agency contesting this urban agenda. Premier John Cain also felt the MMBW was prone to corruption in planning matters.

What seemed to be a logical realignment for more democratically accountable planning has since been shown to be a regrettable move. Direct state control of metropolitan planning and infrastructure is beset by issues of legitimacy, competency and funding.

Read more: All the signs point to our big cities' need for democratic, metro-scale governance

The need for a metropolitan mandate

The state government speaks for the state, not the metropolitan community. Its lack of a metropolitan mandate constrains the government’s legitimacy in resolving conflicting planning objectives – for example, promoting urban consolidation while protecting local amenity. Communities are likely to see the government as unsympathetic to local concerns.

The primary competency of state governments rests in providing jurisdiction-wide services like health, education, policing and justice, which lend themselves to economies of scale and vertical integration. Such operations often unfairly attract the disparaging label “silo”.

State governments are best at serving citizens “at large” rather than citizens “in place”. By contrast, local governments have a natural competency in linking up and leveraging neighbourhood services.

The “silo tendencies” of state governments have to be tempered by investment in new institutions to make sure projects together produce the metropolitan outcome that policies like Plan Melbourne seek. At least five state government agencies have a direct hand in planning Melbourne. Around ten others have co-ordination or oversight roles in urban development.

Understanding how this complex web of institutions works is a challenge for those in the system let alone for ordinary citizens.

In the ten years to 2018, state government employment grew by around 20% in Victoria. In part, this increase reflected investment in project delivery, planning and co-ordination. In local government, which faces similar growth management challenges, employment has been more or less steady since 2010-11.

Read more: Australia, we need to talk about who governs our city-states

What can a commission do that the state can’t?

A metropolitan sphere of governance – working in a similar way to the former MMBW – might offer productivity advantages compared to elaborate administrative reforms within state governments to curb their silo proclivities.

Because they lack a mandate from the metropolitan community, state governments are not well placed to advance particular reforms to improve urban infrastructure.

One example is development licence fees. Increases in land value associated with rezoning and development approvals are the result of good urban governance and citizen-funded infrastructure rather than the efforts of passive land holders. “Value capture” strategies like development fees could raise billions in revenue without distortive effects. However, state leaders rarely canvass such reform.

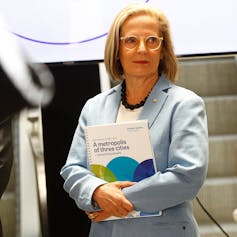

Under Lucy Turnbull’s leadership, the Greater Sydney Commission has a new vision for Sydney.

Danny Casey/AAP

Under Lucy Turnbull’s leadership, the Greater Sydney Commission has a new vision for Sydney.

Danny Casey/AAP

While the state government has a big vision for Melbourne, it lacks the wherewithal to manage metropolitan development towards this end. Stronger institutions for integrated metropolitan governance are needed.

An opening gambit could be to establish a Melbourne Metropolitan Commission, taking on board the experience of the Greater Sydney Commission. It has done a great job of creating a new vision for Sydney, but is ultimately a wholly owned institution of the state government.

Read more: Speaking with: Lucy Turnbull on the Greater Sydney Commission

An effective Melbourne Metropolitan Commission would require at least a partial democratic mandate from the metropolitan community. A minority of seats on its board could be reserved for local council representatives appointed by electoral colleges across the metropolitan region.

As the custodian of Plan Melbourne, the commission would be the planning authority for all parts of the city that are of metropolitan significance. This would include major activity centres, the principal public transport network, the urban growth boundary and the national employment and innovation clusters identified in the plan.

The commission should be the “gatekeeper” that tests potential city-shaping projects against the metropolitan strategy.

The commission would control the public transport and arterial road networks, as well as metropolitan parks and water-cycle management. This place-based governance would be able to unlock synergies and innovations in these systems that have eluded state governments.

The commission might also be able to pursue the case for a fairer sharing of the value that metropolitan development creates.