TV has changed, so must the way we support local content

- Written by Amanda Lotz, Professor of Media Studies, Queensland University of Technology

Australians have enjoyed watching Australian stories on the small screen for generations. From Number 96 to Offspring, House Husbands to Mystery Road, Australian television has reflected Australia back to Australian audiences.

As the government notes in its recent options paper, issued through the Australian Communications and Media Authority and Screen Australia: “Screen stories are uniquely powerful”.

But the future of these stories is in question.

Released at the end of March, the options paper aims to modernise how Australian content is supported. It suggests four options – no change, complete deregulation, minimal change or significant change – with responses due by June 12.

Three of these options would eliminate the local quotas that have underpinned Australian drama, documentary and children’s television production since the late 1960s.

Our research examines the role of television storytelling, especially the importance of local television. So it’s with great surprise we find ourselves advocating for the elimination of Australian content quotas on commercial free-to-air broadcasters.

Instead, we support the model that calls for the creation of a production fund – the “significant change” option – to address the challenges and opportunities currently facing Australian television.

We’re advocating for this change precisely because we think Australian television is so important. Australian drama, documentary and children’s programs, called “Australian story forms” here, deserve better support than currently offered by policies that have well and truly passed their use-by date.

How did we get here?

Much has changed over the past 20 years. Australia’s transition to digital broadcasting saw five existing free-to-air channels increase to at least 25, along with their correlated “catch-up” services such as Iview and 10Play.

Then, subscriber video-on-demand services (SVODs) like Stan and Netflix emerged.

The expansion of the Australian video ecosystem to include new digital channels, catch-up services and SVODs fragmented audiences, and caused advertiser funded Seven, Nine and Ten to come under significant financial pressure.

Read more: Save our screens: 3 things government must do now to keep Australian content alive

Local content quotas

When Australian content quotas were introduced in the late 1960s they applied to the three commercial channels.

These quotas dictated schedules must contain minimum levels of local content, such as documentary and drama, including children’s. At the time, the commercial networks relied on lower-cost imported programs, particularly for children, rather than homegrown drama.

When Foxtel launched in 1995, it too had local obligations, set at 10% of programming costs. SVODs do not broadcast on the public spectrum – the infrastructure that allows us to send wireless signals – and they are not subject to local content quotas. More than 14.5 million Australians pay to access these SVOD services.

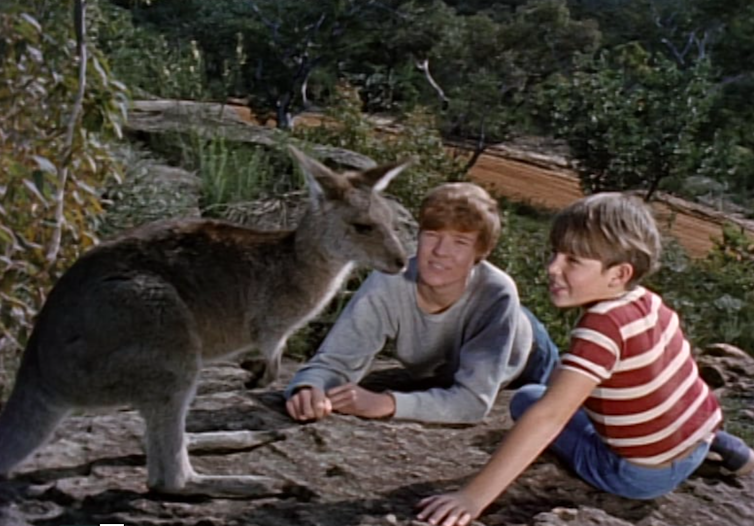

What’s that, Skippy? Content quotas are no longer working to share Australian stories?

NFSA

What’s that, Skippy? Content quotas are no longer working to share Australian stories?

NFSA

The policy paradox

Commercial broadcasters now focus on programming that encourages live viewing – news, sport and reality competitions – because viewers reliably turn up when they air.

All broadcasters have slowed production of Australian story forms, while Seven announced in February it would stop production of children’s content entirely.

Seven’s actions would have put them in breach of local content rules, but the quotas were suspended completely in April in response to COVID-19.

Commercial broadcasters are poorly suited to provide Australian story forms because their business model requires attracting large audiences. But these broadcasters still use the public spectrum and remain protected from competition from additional broadcasters. These advantages must come with obligations.

Australian story forms work very well for television services with different business models, including SVODs and public service broadcasters. Their business models reward the creation of distinctive programs. Multinational SVODs – that serve subscribers in scores of countries – spend only small amounts on Australian content, however. Sustained budget cuts to the ABC and SBS mean they are also forced to commission fewer and shorter series.

Conditions have changed too much for local quotas to be effective. We believe the simplest and most equitable way of solving this paradox is through creating an Australian Production Fund and eliminating quotas.

Seven, Nine and Ten would have to contribute to this fund in return for the benefits they enjoy. Any television services commissioning Australian stories could apply for funding.

This system will simplify the safeguarding of Australian stories.

No clear sides

The commercial broadcasters’ future looks uncertain. Their failure to innovate and add value in the face of increasing audience choices has compounded the challenges of an evolving marketplace.

The requirement to contribute to an Australian Production Fund provides flexibility while maintaining commercial broadcasters’ local content obligations.

A carefully developed Australian Production Fund is our best means of safeguarding Australian stories, for audiences of all ages.

Read more https://theconversation.com/tv-has-changed-so-must-the-way-we-support-local-content-139674