Enforcing assimilation, dismantling Aboriginal families: a history of police violence in Australia

- Written by Thalia Anthony, Professor of Law, University of Technology Sydney

Readers are advised the following article contains descriptions of violence that may be traumatic.

In July 2018, Western Australia’s Police Commissioner Chris Dawson formally apologised for the mistreatment of Aboriginal people at the hands of police, acknowledging the “significant role” the police played in the dispossession of Australia’s First Nations people. Dawson made particular reference to the way:

forceful removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families and communities, the displacement of mothers and their children, sisters, fathers and brothers, the loss of family and resulting destruction of culture has had grave impacts

“Forced removal” references the unique role played by police in many settler colonies such as Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, the United States and Canada in relation to First Nations peoples: executing assimilationist policies designed to dismantle First Nations families.

A closer look at the history of policing in Australia helps explain some of the dynamics at play in the Black Lives Matter and First Nations Deaths in Custody movement in Australia and a growing push for alternative models of policing.

Read more: Was there slavery in Australia? Yes. It shouldn't even be up for debate

The ‘Irish Model’ of policing

Mainstream histories of policing have looked to 19th century British Prime Minister Robert Peel’s London Metropolitan Police “British Model” of policing, with its focus on policing through consensus and “walking the beat”.

There is another model of policing, however, which better reflects the Australian history.

Known as the “Irish Model” from its origins in suppressing dissent in the Irish colony in the 19th century, it set the police against the community, placed them in military style barracks, under a highly centralised and hierarchical chain of command. In general, they were not there to win hearts and minds.

Look to Chris Owen’s magnificent study of policing in the Kimberley region of Western Australia between 1882 and 1905 - titled Every Mother’s Son is Guilty. Policing was based around a highly mobile horse mounted model to cope with the extraordinary distances. As Owen shows, attitudes of the police towards First Nations people were deeply influenced by contemporary beliefs that they were inferior to whites, and a priori criminal.

Many police officers in the frontier colonial era were conscious of being part of a “civilizing mission” and held highly paternalistic attitudes.

One officer who policed the remote regions of Western Australian in the 1920s recalls being

conscientious in my desire for their welfare, for I looked upon them then, as I do now, as children.

Punitive attitudes

Elsewhere, officers exercised often unfettered brutality in punitive frontier expeditions. This was in pursuit of pastoral land grabs, settler occupation and the disintegration of Aboriginal families.

This was a feature of the Native Police Forces that operated in various parts of Australia from the 1830s until the early 20th century.

These forces, responsible for many atrocities against Aboriginal people, consisted of Aboriginal troopers under the command of white officers such as Constable William Willshire whose killings resulted in an unsuccessful murder trial in 1891 and Lieutenant Frederick Wheeler, whose massacres were reviewed by a Queensland parliamentary inquiry in 1861 (which decided to reprimand but not dismiss him).

The inquiry heard evidence of the Native Police Force’s murderous contact with Aboriginal people.

Historical accounts of the Northern Territory’s Native Police, modelled on the Queensland’s Force, documents its fatal force against Aboriginal lives to allegedly defend colonists’ lives and property.

In Western Australia, the 1927 Royal Commission into the killing and burning of Aboriginal bodies in the Forrest River massacre found police were brutal in effecting arrests.

The use of police brutality extended beyond Native Police expeditions, and was characteristic of police powers more widely. The Colonial Frontier Massacres Map documenting massacres of First Nations families across Australia include extensive records of police killings, such as 60 Warlpiri, Anmatyere and Kaytetye women, men and children in the Coniston Massacre in 1928.

Police practices of neck chaining Aboriginal prisoners continued officially into the mid-20th century in parts of Australia.

Read more: Defunding the police could bring positive change in Australia. These communities are showing the way

‘Aboriginal Protection Acts’ were used to control Aboriginal people.

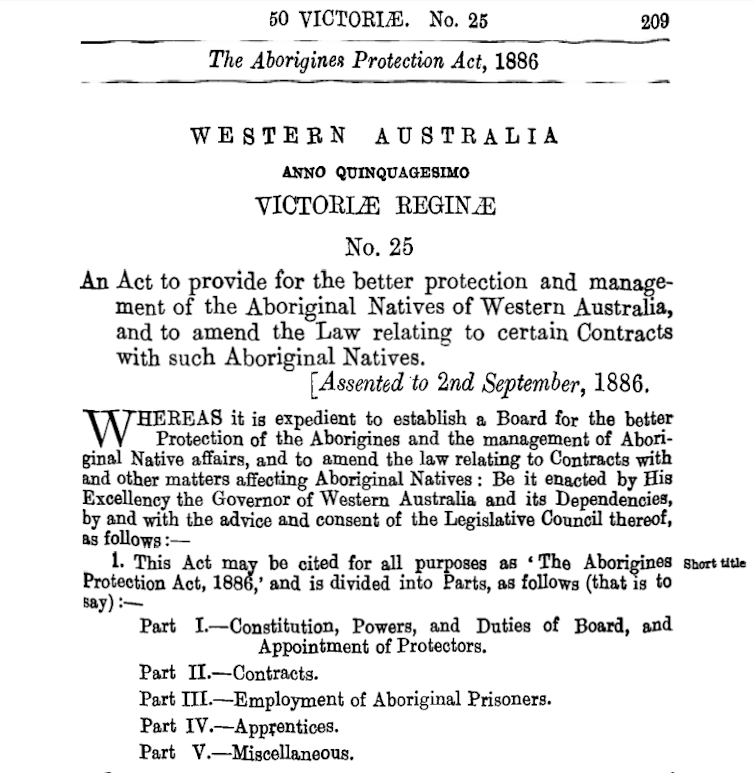

AIATSIS, Author provided

‘Aboriginal Protection Acts’ were used to control Aboriginal people.

AIATSIS, Author provided

‘Protection’

Ideas of law and order formed only a fragment of the colonial police role where Aboriginal people were concerned. Much of it was taken up with implementing the “Aboriginal Protection Acts” or simply “Aboriginal Acts”, which continued well into the 20th century. Examples abound: the Aborigines Protection Act 1886 (Western Australia), the Aboriginal Protection Act and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Queensland), the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (New South Wales), the Aborigines Act 1911 (South Australia); Aboriginals Ordinance 1911 (Northern Territory) and The Aborigines Protection Act 1886 (Victoria).

Aboriginal Acts were used in practice to forcibly relocate Aboriginal people to a place of prescribed confinement, which in practice could include on government settlements, reserves, church missions, hospital lock ups, penal islands, cattle stations and other institutions.

Often police officers assumed the role of Aboriginal Protector under these Acts and exercised broad powers over Aboriginal lives.

Police also gained specific powers under legislation that allowed them to remove Aboriginal children from their families under “child welfare” legislation. Testimony from Victoria in the Bringing them Home inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families reported that:

From 1956 and 1957 more than one hundred and fifty children (more than 10% of the children in the Aboriginal population of Victoria at that time) were living in State children’s institutions. The great majority had been seized by police and charged in the Children’s Court with “being in need of care and protection”. Many policemen act from genuine concern for the “best interests” of Aboriginal children, but some are over-eager to enter Aboriginal homes and bully parents with threats to remove their children.

The experience of one Aboriginal child in Western Australia in 1935 was told to the inquiry:

I was at the post office with my Mum and Auntie [and cousin]. They put us in the police ute and said they were taking us to Broome. They put the mums in there as well. But when we’d gone [about ten miles] they stopped, and threw the mothers out of the car. We jumped on our mothers’ backs, crying, trying not to be left behind. But the policemen pulled us off and threw us back in the car. They pushed the mothers away and drove off, while our mothers were chasing the car, running and crying after us. We were screaming in the back of that car. When we got to Broome they put me and my cousin in the Broome lock-up. We were only ten years old.

Police still play a role in removing First Nations children from their families today. The Family is Culture Report in 2019 noted significant concerns about the use of police during removals, saying:

when police are used for removal, especially riot police, this has historical continuity.

Police powers in the first half of the 20th century extended to the forced isolation and confinement of Aboriginal people on public health grounds, such as in various lock-up hospitals, on the basis of a diagnosis made by a police officer of syphilis or leprosy - or a decision that the person was at risk.

The police acted as the gatekeepers for enclosure in a ubiquity of institutions. At the same time as imposing the law, the police also acted as Protectors of Aboriginal people, distributed rations and blankets, provided pastoralists with Aboriginal workers in remote areas and ensured that they remained on pastoral stations.

Aboriginal worker Hobbles Danyarri said:

If you put your own colour, police tracker, that means he can bring them in. He can bring them in to work and don’t let him steal it [beef]. Let them work. Let them work.

And Aboriginal stockman Barney Barnes remembers the removal of Aboriginal communities accused of cattle killing onto Cherrabun, Go Go and Christmas Creek stations in the Kimberley:

That manager made the police go out and bring all the people in from the desert. He reckoned that they were killing too many bullocks. So the police came out and rounded up all the Walmajarri people […] They kept going at it until nobody was left out there. They didn’t allow the Aboriginal people to live in the desert after that.

Aboriginal people who defied Aboriginal Protection Acts and the rules of reserves and settlements - such as speaking in language, practising culture, marrying without the protector’s permission, or otherwise disobeying orders of the protector - would be sent for punishment to places such as Palm Island. These Acts were often enforced by police officers.

Hope for the future

Moving away from a colonial and assimilationist model of policing in Australia involves restructuring police and honouring First Nations self determination.

Community Patrol models, which are embedded in First Nations communities and work towards the safety and wellbeing of women, children and families, provide a First Nations alternative.

It’s time to consider setting police models on a new course that abolishes force and re-imagines community relationships.

UPDATE: This story has been updated to add more detail and quotes.