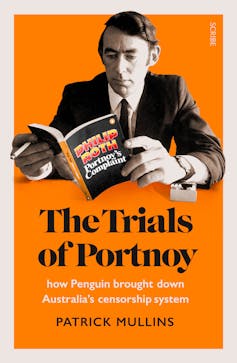

Trials of Portnoy: when Penguin fought for literature and liberty

- Written by Patrick Mullins, Adjunct assistant professor, Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra

One grey morning in October 1970, in a crowded, tizzy-pink courtroom on the corner of Melbourne’s Russell and La Trobe Streets, crown prosecutor Leonard Flanagan began denouncing a novel in terms that were strident and ringing.

“When taken as a whole, it is lewd,” he declared. “As to a large part of it, it is absolutely disgusting both in the sexual and other sense; and the content of the book as a whole offends against the ordinary standards of the average person in the community today – the ordinary, average person’s standard of decency.”

Scribe

The object of Flanagan’s ire that day was the Penguin Books Australia edition of Portnoy’s Complaint. Frank, funny, and profane, Philip Roth’s novel — about a young man torn between the duties of his Jewish heritage and the autonomy of his sexual desires — had been a sensation the world over when it was published in February 1969.

Greeted with sweeping critical acclaim, it was advertised as “the funniest novel ever written about sex” and called “the autobiography of America” in the Village Voice. In the United States, it sold more than 400,000 copies in hardcover in a single year — more, even, than Mario Puzo’s The Godfather — and in the United Kingdom it was published to equal fervour and acclaim.

But in Australia, Portnoy’s Complaint had been banned.

Read more:

Philip Roth was the best post-war American writer, no ifs or buts

Banned books

Politicians, bureaucrats, police, and judges had for years worked to keep Australia free of the moral contamination of impure literature. Under a system of censorship that pre-dated federation, works that might damage the morals of the Australian public were banned, seized, and burned. Bookstores were raided. Publishers were policed and fined. Writers had been charged, fined and even jailed.

Seminal novels and political tracts from overseas had been kept out of the country. Where objectionable works emerged from Australian writers, they were rooted out like weeds. Under the censorship system, Boccacio’s Decameron had been banned. Nabokov’s Lolita had been banned. Joyce’s Ulysses had been banned. Even James Bond had been banned.

There had been opposition to this censorship for years, though it had become especially notable in the past decade. Criticism of the bans on J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Norman Lindsay’s Redheap had prompted an almost complete revision of the banned list in 1958.

The repeated prosecutions of the Oz magazine team in 1963 and 1964 had attracted enormous attention and controversy.

Outcry over the bans on Mary McCarthy’s The Group and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been loud and pronounced, and three intrepid Sydney activists had exposed the federal government to ridicule when they published a domestic edition of The Trial of Lady Chatterley, an edited transcript of the failed court proceedings against Penguin Books UK for the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Britain in 1960.

Read more:

Friday essay: the Melbourne bookshop that ignited Australian modernism

Penguin goes to battle

Penguin Books Australia had been prompted to join the fight against censorship by the three idealistic and ambitious men at its helm: managing director John Michie, finance director Peter Froelich, and editor John Hooker.

In five years, the three men had overhauled the publisher, improving its distribution machinery and logistics and reinvigorating its publishing list. They believed Penguin could shape Australian life and culture by publishing interesting and vibrant books by Australian authors.

They wanted Penguin’s books to engage with the political and cultural shifts that the country was undergoing, to expose old canards, question the orthodox, and pose alternatives.

Censorship was no small topic in all this. Those at Penguin saw censorship as an inhibition on these ambitions. “We’d had issues with it before, in minor ways,” Peter Froelich recalled, “and we’d have drinks we’d say, ‘It’s wrong! How can we fix it? What can we do? How do we bring it to people’s attention, so that it can be changed?’”

The answer emerged when they heard of the ban placed on Portnoy’s Complaint. Justifiably famous, a bestseller the world over, of well-discussed literary merit, it stood out immediately as a work with which to challenge the censorship system, just as its British parent company had a decade earlier.

Why not obtain the rights to an Australian edition, print it in secret, and publish it in one fell swoop? As Hooker — who had the idea — put it to Michie, “Jack, we ought to really publish Portnoy’s Complaint and give them one in the eye”.

The risks were considerable. There was sure to be a backlash from police and politicians. Criminal charges against Penguin and its three leaders were almost certain. Financial losses thanks to seized stock and fines would be considerable. The legal fees incurred in fighting charges would be enormous. Booksellers who stocked the book would also be put on trial. But Penguin was determined.

John Michie was resolute. “John offered to smash the whole thing down,” Hooker said, later. When he was told what was about to happen, federal minister for customs Don Chipp swore that Michie would pay: “I’ll see you in jail for this.” But Michie was not to be dissuaded.

‘People who took exception to it at the time are mostly dead,’ Roth said, some 40 years and 30 books after Portnoy’s Complaint was published.A stampede

In July 1970, Penguin arranged to have three copies of Portnoy smuggled into Australia. In considerable secrecy, they used them to print 75,000 copies in Sydney and shipped them to wholesalers and bookstores around the country. It was an operation carried out with a precision that Hooker later likened to the German invasion of Poland.

Scribe

The object of Flanagan’s ire that day was the Penguin Books Australia edition of Portnoy’s Complaint. Frank, funny, and profane, Philip Roth’s novel — about a young man torn between the duties of his Jewish heritage and the autonomy of his sexual desires — had been a sensation the world over when it was published in February 1969.

Greeted with sweeping critical acclaim, it was advertised as “the funniest novel ever written about sex” and called “the autobiography of America” in the Village Voice. In the United States, it sold more than 400,000 copies in hardcover in a single year — more, even, than Mario Puzo’s The Godfather — and in the United Kingdom it was published to equal fervour and acclaim.

But in Australia, Portnoy’s Complaint had been banned.

Read more:

Philip Roth was the best post-war American writer, no ifs or buts

Banned books

Politicians, bureaucrats, police, and judges had for years worked to keep Australia free of the moral contamination of impure literature. Under a system of censorship that pre-dated federation, works that might damage the morals of the Australian public were banned, seized, and burned. Bookstores were raided. Publishers were policed and fined. Writers had been charged, fined and even jailed.

Seminal novels and political tracts from overseas had been kept out of the country. Where objectionable works emerged from Australian writers, they were rooted out like weeds. Under the censorship system, Boccacio’s Decameron had been banned. Nabokov’s Lolita had been banned. Joyce’s Ulysses had been banned. Even James Bond had been banned.

There had been opposition to this censorship for years, though it had become especially notable in the past decade. Criticism of the bans on J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Norman Lindsay’s Redheap had prompted an almost complete revision of the banned list in 1958.

The repeated prosecutions of the Oz magazine team in 1963 and 1964 had attracted enormous attention and controversy.

Outcry over the bans on Mary McCarthy’s The Group and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been loud and pronounced, and three intrepid Sydney activists had exposed the federal government to ridicule when they published a domestic edition of The Trial of Lady Chatterley, an edited transcript of the failed court proceedings against Penguin Books UK for the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Britain in 1960.

Read more:

Friday essay: the Melbourne bookshop that ignited Australian modernism

Penguin goes to battle

Penguin Books Australia had been prompted to join the fight against censorship by the three idealistic and ambitious men at its helm: managing director John Michie, finance director Peter Froelich, and editor John Hooker.

In five years, the three men had overhauled the publisher, improving its distribution machinery and logistics and reinvigorating its publishing list. They believed Penguin could shape Australian life and culture by publishing interesting and vibrant books by Australian authors.

They wanted Penguin’s books to engage with the political and cultural shifts that the country was undergoing, to expose old canards, question the orthodox, and pose alternatives.

Censorship was no small topic in all this. Those at Penguin saw censorship as an inhibition on these ambitions. “We’d had issues with it before, in minor ways,” Peter Froelich recalled, “and we’d have drinks we’d say, ‘It’s wrong! How can we fix it? What can we do? How do we bring it to people’s attention, so that it can be changed?’”

The answer emerged when they heard of the ban placed on Portnoy’s Complaint. Justifiably famous, a bestseller the world over, of well-discussed literary merit, it stood out immediately as a work with which to challenge the censorship system, just as its British parent company had a decade earlier.

Why not obtain the rights to an Australian edition, print it in secret, and publish it in one fell swoop? As Hooker — who had the idea — put it to Michie, “Jack, we ought to really publish Portnoy’s Complaint and give them one in the eye”.

The risks were considerable. There was sure to be a backlash from police and politicians. Criminal charges against Penguin and its three leaders were almost certain. Financial losses thanks to seized stock and fines would be considerable. The legal fees incurred in fighting charges would be enormous. Booksellers who stocked the book would also be put on trial. But Penguin was determined.

John Michie was resolute. “John offered to smash the whole thing down,” Hooker said, later. When he was told what was about to happen, federal minister for customs Don Chipp swore that Michie would pay: “I’ll see you in jail for this.” But Michie was not to be dissuaded.

‘People who took exception to it at the time are mostly dead,’ Roth said, some 40 years and 30 books after Portnoy’s Complaint was published.A stampede

In July 1970, Penguin arranged to have three copies of Portnoy smuggled into Australia. In considerable secrecy, they used them to print 75,000 copies in Sydney and shipped them to wholesalers and bookstores around the country. It was an operation carried out with a precision that Hooker later likened to the German invasion of Poland.

Wikimedia

The book was unveiled on August 31 1970. Michie held a press conference in his Mont Albert home, saying Portnoy’s Complaint was a masterpiece and should be available to read in Australia. Neither he nor Penguin were afraid of the prosecutions: “We are prepared to take the matter to the High Court.”

The next morning, as the trucks bearing copies began to arrive, bookstores everywhere were rushed. At one Melbourne bookstore, the assistant manager was knocked down and trampled by a crowd eager to buy the book and support Penguin. “It was a stampede,” he said later. A bookstore manager in Sydney was amazed when the 500 copies his store took sold out in two-and-a-half hours.

All too soon, it was sold out. And with politicians making loud promises of retribution, the police descended.

Bookstores were raided. Unsold copies were seized. Court summons were delivered to Penguin, to Michie, and to booksellers the whole country over. A long list of court trials over the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint and its sale were in the offing.

A stellar line-up

So the trial that opened on the grey morning of October 19 1970, in the Melbourne Magistrates Court, was only the first in what promised to be a long battle.

Neither Michie nor his colleagues were daunted. They had prepared a defence based around literary merit and the good that might come from reading the book. They had retained expert lawyers and marshalled the cream of Australia’s literary and academic elite to come to their aid.

Patrick White would appear as a witness for the defence. So too would academic John McLaren, The Age newspaper editor Graham Perkin, the critic A.A. Phillips, the historian Manning Clark, the poet Vincent Buckley, and many more. They were unconcerned by Flanagan’s furious denunciations, by his shudders of disgust, and by his caustic indictments of Penguin and its leaders.

They were confident in their cause. As one telegram to Michie said:

ALL BEST WISHES FOR A RESOUNDING VICTORY FOR LITERATURE AND LIBERTY.

This is an edited extract from Trials of Portnoy by Patrick Mullins, published by Scribe.

Wikimedia

The book was unveiled on August 31 1970. Michie held a press conference in his Mont Albert home, saying Portnoy’s Complaint was a masterpiece and should be available to read in Australia. Neither he nor Penguin were afraid of the prosecutions: “We are prepared to take the matter to the High Court.”

The next morning, as the trucks bearing copies began to arrive, bookstores everywhere were rushed. At one Melbourne bookstore, the assistant manager was knocked down and trampled by a crowd eager to buy the book and support Penguin. “It was a stampede,” he said later. A bookstore manager in Sydney was amazed when the 500 copies his store took sold out in two-and-a-half hours.

All too soon, it was sold out. And with politicians making loud promises of retribution, the police descended.

Bookstores were raided. Unsold copies were seized. Court summons were delivered to Penguin, to Michie, and to booksellers the whole country over. A long list of court trials over the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint and its sale were in the offing.

A stellar line-up

So the trial that opened on the grey morning of October 19 1970, in the Melbourne Magistrates Court, was only the first in what promised to be a long battle.

Neither Michie nor his colleagues were daunted. They had prepared a defence based around literary merit and the good that might come from reading the book. They had retained expert lawyers and marshalled the cream of Australia’s literary and academic elite to come to their aid.

Patrick White would appear as a witness for the defence. So too would academic John McLaren, The Age newspaper editor Graham Perkin, the critic A.A. Phillips, the historian Manning Clark, the poet Vincent Buckley, and many more. They were unconcerned by Flanagan’s furious denunciations, by his shudders of disgust, and by his caustic indictments of Penguin and its leaders.

They were confident in their cause. As one telegram to Michie said:

ALL BEST WISHES FOR A RESOUNDING VICTORY FOR LITERATURE AND LIBERTY.

This is an edited extract from Trials of Portnoy by Patrick Mullins, published by Scribe.

Read more https://theconversation.com/trials-of-portnoy-when-penguin-fought-for-literature-and-liberty-141525