There are many ways to achieve Indigenous recognition in the constitution – we must find one we can agree on

- Written by Anne Twomey, Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Sydney

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was the culmination of consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the country. Many voices were distilled into one united voice about how to proceed with the constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians.

While its momentous historic importance is well recognised, attempts to give effect to it have been bogged down in dispute and bureaucratic malaise.

In 2015, I suggested a draft constitutional amendment that would have given effect to an Indigenous voice to parliament. It remains my preferred option because it is simple, clear and fair. It would also avoid the interference of courts by making the consideration of advice a matter of internal parliamentary affairs.

But a constitutional amendment that entrenched a voice to parliament was rejected at the political level due to unfounded concerns it would become a “third chamber of parliament”.

While even Barnaby Joyce eventually accepted this was wrong, the political objections to this proposal have proved hard to shift.

Read more: The Uluru statement showed how to give First Nations people a real voice – now it's time for action

In the absence of political movement, it may be time to think about other means of giving effect to the Uluru Statement that are consistent with its spirit and offer prospects of success.

How else could constitutional amendments be formulated to achieve this outcome?

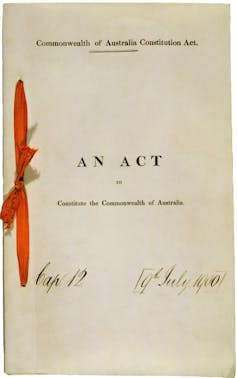

Amending the race power

One option is to amend the race power in section 51(xxvi) of the constitution. It currently provides that the Commonwealth Parliament has the power to make laws with respect to

the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.

Given that, in practice, this provision has only been used to make laws with respect to Indigenous Australians, it could be amended to allow parliament to make laws with respect to:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs; and in relation thereto, the interaction between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the Parliament and Government of the Commonwealth.

The archaic style of drafting is intended to be consistent with that of other constitutional powers, although the language could be modernised. A more detailed explanation of the drafting rationale is here for those who wish to assess its merits.

The express reference to “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” is intended to provide a form of constitutional recognition. It recognises their standing to interact with the parliament and the government.

“Interaction” is a broad term, which could be given effect by a variety of means. This provision better reflects the intent of the Uluru Statement. It would not only accommodate interaction by means of a Voice to parliament, but also a Makarrata Commission, treaty-making, agreement-making and truth-telling.

The proposed amendment makes no reference to a representative body. This avoids any perceived problems with constitutionalising its description or nature.

Rather, the interaction is between the “peoples” and the parliament and government. This could be done through the creation of bodies, or by other means. Critically, there is nothing in the amendment that could be characterised as a third chamber of parliament.

Indigenous recognition in the constitution will not lead to a ‘third chamber’ of parliament.

AAP/Lucas Coch

Indigenous recognition in the constitution will not lead to a ‘third chamber’ of parliament.

AAP/Lucas Coch

There is no legal obligation to establish the means of interaction. But the approval by the people, in a referendum, of a power that expressly provides for making these laws would create a political imperative for action.

There are, however, two problems with this approach. First, the 1967 referendum and the amendments it made to the race power are iconic for Indigenous Australians, who are reluctant to alter that legacy. Second, section 51 merely facilitates legislative action – it contains no sense of an obligation to act.

A stand-alone amendment

An alternative approach would be to enact a stand-alone provision that does contain an obligation, but leaves to parliament and the government flexibility about the means to achieve it. Such an amendment could provide as follows:

The Commonwealth shall make provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be heard by the Commonwealth regarding proposed laws and other matters with respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, and the Parliament may make laws to give effect to this provision.

This approach, which is modelled on sections 119 and 120 of the constitution, places the obligation in the right place. It is the Commonwealth of Australia – the nation as a whole – that is obliged to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are heard in relation to their own affairs. But it leaves open the means of giving effect to that obligation – it could be by government action, legislation, a parliamentary committee, or a combination of all of them.

It could also encompass co-operative Commonwealth and state action so Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have their voices heard by all constituent parts of the nation.

This draft amendment would provide constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and permit them to be heard in a range of different ways. Parliament would retain flexibility in determining how this should be done, but there would still be an obligation to act.

There are several ways the constitution might be amended.

Parliamentary Education Office

There are several ways the constitution might be amended.

Parliamentary Education Office

That obligation would be a constitutional duty and a political obligation, but not a legally enforceable one. In legal terms, it would be described as a “duty of imperfect obligation”.

Under this proposed section 127, a court would have no power to instruct the parliament to enact a law or compel the government to give effect to the duty. These would be matters for the parliament and government to decide. But a political and constitutional duty would exist nonetheless, which a responsible government could not ignore.

In terms of the legacy of 1967, such an amendment would retain, untouched, the race power in section 51(xxvi). But it could fill the gap resulting from the repeal of section 127 in 1967. This was the provision that had excluded Aboriginal people from being counted in reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth for certain purposes. It is fitting that it be replaced with a provision that counts the value of Aboriginal people by insisting they be heard.

The way forward

There are many ways the constitution might be amended to give effect to the Uluru Statement. Failure to convince the government as to the merits of one of them does not mean all hope should be abandoned.

Other options are yet to be explored. For example, groups such as Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition are also working on proposals for constitutional change, which need to be considered.

Above are two draft amendments that can serve to reopen the debate. It is time for people of good will to come to the table with proposals to see if the Uluru Statement can be taken to heart by the Commonwealth and reflected in its constitution.