Every state is about to dole out federal funding for broadband internet – not every state is ready for the task

- Written by Brian Whitacre, Professor and Neustadt Chair, Department of Agricultural Economics, Oklahoma State University

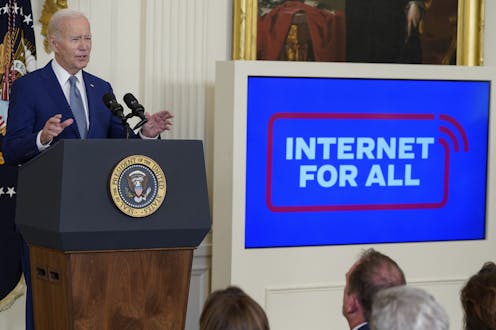

The Biden administration set the amounts of federal funding each state will receive to expand access to broadband internet.AP Photo/Evan Vucci

The Biden administration set the amounts of federal funding each state will receive to expand access to broadband internet.AP Photo/Evan VucciWhen the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was signed in late 2021, it included US$42.5 billion for broadband internet access as part of the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program. The program aims to ensure that broadband access is available throughout the country. This effort differs from previous federal broadband programs because it promised to allocate the funding to individual states and allow them to figure out the best way to distribute it.

Nearly two years later, the federal government informed the states exactly how much money each will be getting. The sizes of the awards are significant: 19 states will receive over $1 billion, and the average award across the 50 states is $817 million. Texas received the largest allocation at over $3.3 billion.

The states are working with the federal government to develop plans for how they will distribute those funds. The states have until Dec. 27, 2023, to submit their initial proposals. As of Nov. 15, no state had completed that process.

Even after the states receive the federal funding, it’s expected to take years for the states to award contracts to internet service providers to install the broadband networks and for the companies to complete the work. States are also in something of a race with one another: The first ones to the funding can get money to the private sector, which can begin hiring from the limited pool of technicians capable of installing fiber optic cables.

Plans and deadlines

An estimated 11.8 million locations – households and businesses, rural and urban – are considered either unserved or underserved. Unserved locations are those where providers only offer internet speeds below 25Mbps downstream and 3Mbps upstream. Underserved locations are those where providers offer internet speeds below 100Mbps downstream and 20Mbps upstream.

Each state’s plans for how to get broadband service to those locations must be approved by the overseeing organization, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. The plans must include information on existing broadband funding that has yet to be deployed from otherfederalprograms, plans for handling challenges, plans to coordinate with tribal and regional entities, how the state will address the need to recruit and train workers to install broadband, and how it will address the issue of broadband affordability. States’ initial proposals can be viewed online.

A dashboard the federal government recently released summarizes the progress made by all 50 states plus U.S. territories in getting these plans approved and receiving the first chunk of the promised funding. Some states are further along than others.

The dashboard includes eight steps each state or territory must complete before getting the first 20% of its promised allocation. As of Nov. 15, 2023, most states had completed four of the process’s eight steps. Only three states – Louisiana, Nevada and Virginia – had finished six or more steps. Notably, Louisiana and Virginia had broadband offices up and running for at least three years prior to the passage of the infrastructure legislation in 2021.

With the due date for submitting plans Dec. 27 and a public comment period that’s required to be open for 30 days, many states could be pushing the deadline. States that miss the deadline could lose out on the funding. States are likely to begin distributing their broadband funds sometime in 2024, and implementation of the plans is expected to take four years.

There are real-world impacts related to which states receive funding first. The vast majority of the funds are expected to be spent on fiber-optic infrastructure, and the telecom industry has concerns about the availability of technicians to install it. One recent survey also found that 20% of the expected hires will be for engineer or manager positions.

Internet providers that successfully apply for grants in one state may quickly hire a larger percentage of available local technicians and engineers, leaving neighboring states with an even larger workforce gap. Along the same lines, most broadband projects require specific types of equipment, which will be in high demand once the money starts flowing.

Other state-level funds

It is important to note that there are other ongoing state-level broadband infrastructure programs. In particular, the 2021 American Recovery Plan Act provided State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds and Capital Projects Funds to each state, many of which have been used for broadband purposes.

While no state-level summary of these projects exists, to the best of my knowledge, they often include significant amounts of money. For example, Missouri recently awarded $261 million from the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Program for broadband projects and another $197 million in Capital Projects funds. Combined, this adds another $458 million to the $1.7 billion that Missouri will be receiving from the broadband program. This $458 million comes with shorter turnaround times than the broadband funds because they were allocated under the American Recovery Plan Act and those funds must be spent by the end of 2026.

Additionally, the broadband program included $2.7 billion for digital equity work, and states have been developing these plans as well. The Digital Equity Act programs aim to ensure that all Americans have access to the skills and technology needed to function in the digital economy. The deadline for state digital equity plans varies by state, but the original timeline calls for awards to be made in 2024. Most of these awards are expected to go to community-based entities (libraries, nonprofits, religious organizations, etc.) to help people gain digital skills.

Lots of work left to do

Once states receive their broadband funding, they still have to set up a mechanism to request proposals from internet service providers, grade the proposals that come in, and oversee the challenge process for rejected proposals that is likely to follow. Some of the initial 20% of the funding that states receive will be used for those purposes. Only after the awards are made and challenges settled will the providers ramp up their workforces, purchase the relevant equipment and begin work.

So while the broadband funding holds great promise for the 11.2 million locations across the country that do not have access to a high-quality broadband connection, many still have a long wait ahead of them.

Brian Whitacre has received funding from USDA Rural Utilities Service, USDA Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Regional Rural Development Centers, Association of Public Land-Grant Universities, Nebraska College of Law, Institute of Museum and Library Services, Health Research Services Administration, the National Science Foundation, the Benton Foundation, and the NTCA (Rural Broadband Association).

Authors: Brian Whitacre, Professor and Neustadt Chair, Department of Agricultural Economics, Oklahoma State University