Chlorine is a highly useful chemical that's also extremely dangerous − here's what to know about staying safe around it

- Written by Aliasger K. Salem, Associate Vice President for Research and Bighley Chair and Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Iowa

Jordanian forensics experts inspect the site of a chlorine gas explosion in the Port of Aqaba in June 2022. Khalil Mazraawi/AFP via Getty Images

Jordanian forensics experts inspect the site of a chlorine gas explosion in the Port of Aqaba in June 2022. Khalil Mazraawi/AFP via Getty ImagesMany people encounter chlorine in their daily lives, whether it’s as an ingredient in household bleach or an additive that sanitizes water in swimming pools. Chlorine is also used as an antiseptic, a bleaching agent in the production of paper and cloth, and to kill microorganisms in drinking water.

But this familiar chemical is also extremely toxic. And because it’s ubiquitous in many industries across the U.S., it often is released in chemical accidents and spills.

As a pharmaceutical scientist, I study ways in which chemicals and other materials affect the human body. Currently, I am working to develop therapies to counteract chlorine gas exposure and to understand the mechanism by which chlorine harms people. One promising therapy that we are developing is inhalable nanoparticles that counteract lung damage following chlorine gas exposure.

A common and dangerous chemical

Chlorine is an extremely toxic and widely used chemical. In the U.S., it is one of the top five chemicals by production volume, with an output of about 12 million tons (11 million metric tons) per year.

A yellow-green gas at room temperature, chlorine is highly reactive, which means that it readily forms compounds with many other chemicals. These reactions often are very intense. Chlorine reacts explosively or forms explosive compounds with many common substances, including hydrogen, turpentine and ammonia.

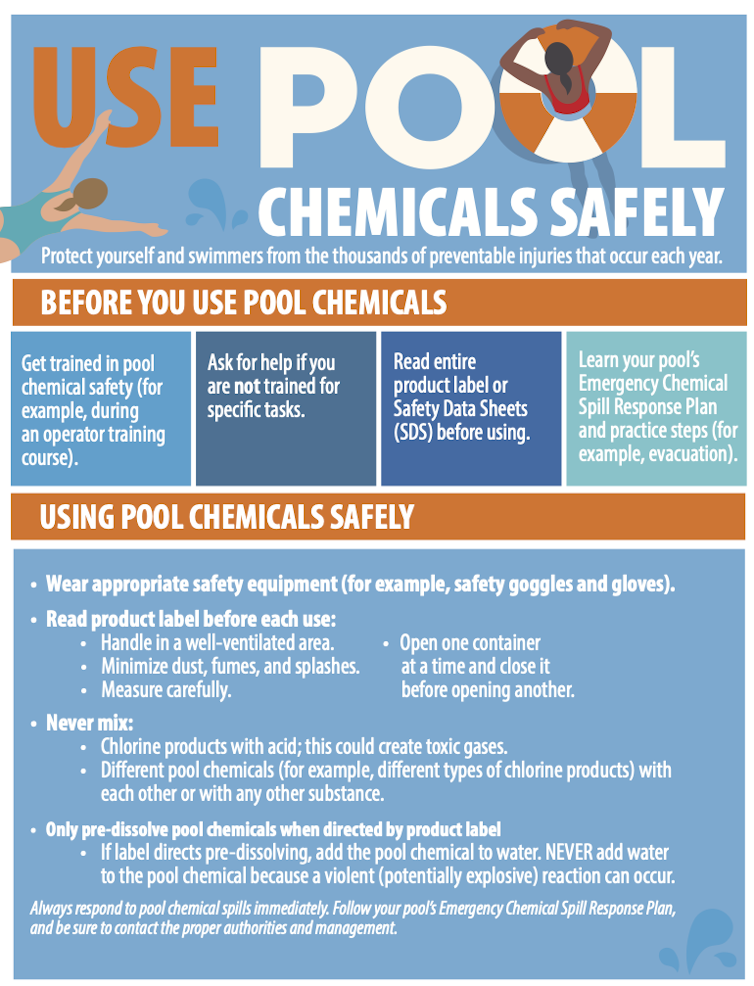

Even in everyday uses, chlorine requires special handling and precautions.CDC

Even in everyday uses, chlorine requires special handling and precautions.CDCChlorine gas exposure, even for short periods of time and at low levels, leads to eye, throat and nose irritation and causes coughing and breathing problems and burning in the eyes. Higher exposure levels can cause chest pain, severe breathing difficulties, pneumonia, vomiting and fluid in the lungs. Very high levels can cause death. Chlorine also can be absorbed through the skin, resulting in pain, swelling, inflammation and blistering.

Our research has shown that exposure to chlorine gas leads to airway inflammation and airway hyperreactivity – swelling and narrowing of the bronchial tubes that carry air to and from your lungs, which makes it harder to breathe. This condition is a characteristic feature of asthma.

Chlorine’s toxicity made it one of the first chemical weapons used on a large scale in warfare. German troops released it against French and Canadian forces in World War I. More recently, international observers report that Syria has used chlorine weapons repeatedly in that country’s civil war. In Iraq, insurgents used chlorine bombs against U.S. forces in 2007 in and around Baghdad, and the Islamic State reportedly later used chlorine in crude roadside bombs in Iraq.

Large-scale releases worldwide

Some recent accidents show how commonly the release or mishandling of chlorine can create life-threatening situations. For example, on April 27, 2023, five workers at a spa in Brooklyn were hospitalized after employees mixed two cleaning chemicals, releasing chlorine gas – a reaction that is surprisingly easy to generate.

A fire burns at the BioLab Inc. chemical plant in Westlake, La., on Aug. 27, 2020. Winds from Hurricane Laura damaged several buildings, and rainwater reached the chemicals stored there, triggering a fire that released a chlorine plume. The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board later concluded that the facility was not adequately prepared for extreme weather.AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

A fire burns at the BioLab Inc. chemical plant in Westlake, La., on Aug. 27, 2020. Winds from Hurricane Laura damaged several buildings, and rainwater reached the chemicals stored there, triggering a fire that released a chlorine plume. The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board later concluded that the facility was not adequately prepared for extreme weather.AP Photo/Gerald HerbertIn a larger event, on April 18, 2022, a compressor fire caused a chlorine gas spill inside a Dow Chemicals facility close to Plaquemine, Louisiana. Liquid chlorine quickly vaporized into the air and spread into adjoining neighborhoods. At least 23 people were hospitalized.

Large-scale shipments of chlorine can cause widespread injuries and even deaths in the event of accidents. For example, when a freight train derailed in Graniteville, South Carolina, in 2005, a tanker car ruptured and released 60 tons of chlorine. Nine people died, 72 were hospitalized and 525 received outpatient medical treatment.

The most dramatic recent case occurred at the Port of Aqaba in Jordan on June 27, 2022. A crane dropped a container loaded with 25 tons of chlorine onto a docked ship, where it broke and produced a massive release of toxic gas. The spill killed 13 people and injured more than 260.

A deadly cloud of chlorine fumes was released after a tank fell onto the deck of a ship while being moved in the Jordanian Port of Aqaba on June 27, 2022.Protecting people from chlorine gas exposure

Although the risks from chlorine gas exposure have been well understood for over a century, there are no current antidotes. This is because chlorine is a strong oxidizing agent that can cause major tissue damage in the body.

People who handle chlorine in the workplace should use respiratory equipment that meets federal regulatory standards. They also should have rubber gloves, a protective apron or other protective clothing, goggles or a face mask, and access to a shower and eye-washing station.

Signs that chlorine may be present include a pungent, irritating odor, like very strong cleaning products; a yellowish-green gas; and irritation to the eyes and throat. If you suspect that you may have been exposed to chlorine gas, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend moving away from the area and removing all clothing and showering if possible.

Symptoms of chlorine exposure can be treated in a hospital. Therapies include providing patients with humidified oxygen, which is less irritating to the nose and throat than conventional oxygen, and inhaled beta-adrenergic agents – medications that are widely used to manage bronchial asthma by relieving lung spasms and reducing airway resistance.

Researchers are studying other medications that may help reduce the severity of lung injury and help patients recover lung function. These include inhalable therapies that reduce lung damage following chlorine gas exposure and oral tablets or injectable therapies that reduce lung inflammation.

Chlorine is a safe and effective disinfectant when handled appropriately. But as with other household chemicals, it is very important to understand its risks, read labels before using it, store it in its original container in a secure place and dispose of it safely.

Aliasger K. Salem receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. He serves on the Executive Board of the American Association for Pharmaceutical Scientists.

Authors: Aliasger K. Salem, Associate Vice President for Research and Bighley Chair and Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Iowa