America’s dairy farms are disappearing, down 95% since the 1970s − milk price rules are one reason why

- Written by Elizabeth Eckelkamp, Associate Professor of Animal Science and Dairy Extension Specialist, University of Tennessee

Running a dairy farm isn't easy, especially when the costs of production rise faster than income.AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall

Running a dairy farm isn't easy, especially when the costs of production rise faster than income.AP Photo/Charlie NeibergallMilton Orr looked across the rolling hills in northeast Tennessee. “I remember when we had over 1,000 dairy farms in this county. Now we have less than 40,” Orr, an agriculture adviser for Greene County, Tennessee, told me with a tinge of sadness.

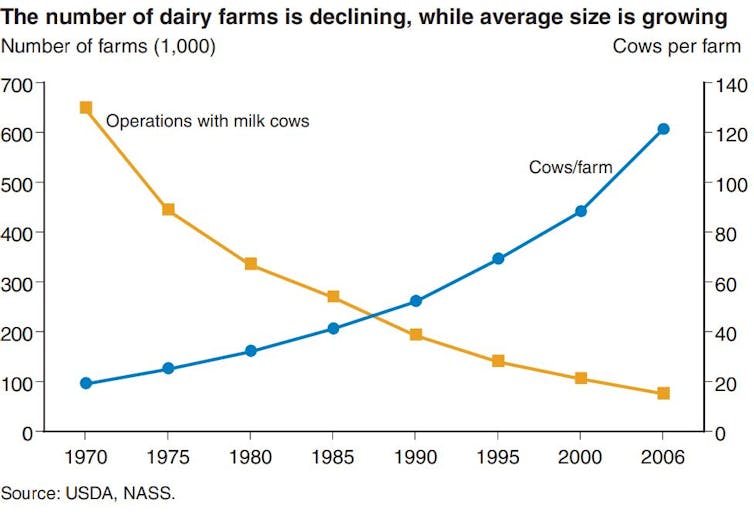

That was six years ago. Today, only 14 dairy farms remain in Greene County, and there are only 125 dairy farms in all of Tennessee. Across the country, the dairy industry is seeing the same trend: In 1970, over 648,000 U.S. dairy farms milked cattle. By 2022, only 24,470 dairy farms were in operation.

While the number of dairy farms has fallen, the average herd size – the number of cows per farm – has been rising. Today, more than 60% of all milk production occurs on farms with more than 2,500 cows.

Dairy farm numbers have fallen over the past few decades, but larger farms have kept the overall number of cows fairly steady.USDA

Dairy farm numbers have fallen over the past few decades, but larger farms have kept the overall number of cows fairly steady.USDAThis massive consolidation in dairy farming has an impact on rural communities. It also makes it more difficult for consumers to know where their food comes from and how it’s produced.

As a dairy specialist at the University of Tennessee, I’m constantly asked: Why are dairies going out of business? Well, like our friends’ Facebook relationship status, it’s complicated.

The problem with pricing

The biggest complication is how dairy farmers are paid for the products they produce.

In 1937, the Federal Milk Marketing Orders, or FMMO, were established under the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act. The purpose of these orders was to set a monthly, uniform minimum price for milk based on its end use and to ensure that farmers were paid accurately and in a timely manner.

Farmers were paid based on how the milk they harvested was used, and that’s still how it works today.

Does it become bottled milk? That’s Class 1 price. Yogurt? Class 2 price. Cheddar cheese? Class 3 price. Butter or powdered dry milk? Class 4. Traditionally, Class 1 receives the highest price.

Do you know where your milk comes from?AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki

Do you know where your milk comes from?AP Photo/Sue OgrockiThere are 11 FMMOs that divide up the country. The Florida, Southeast and Appalachian FMMOs focus heavily on Class 1, or bottled, milk. The other FMMOs, such as Upper Midwest and Pacific Northwest, have more manufactured products such as cheese and butter.

For the past several decades, farmers have generally received the minimum price. Improvements in milk quality, milk production, transportation, refrigeration and processing all led to greater quantities of milk, greater shelf life and greater access to products across the U.S. Growing supply reduced competition among processing plants and reduced overall prices.

Along with these improvements in production came increased costs of production, such as cattle feed, farm labor, veterinary care, fuel and equipment costs.

Researchers at the University of Tennessee in 2022 compared the price received for milk across regions against the primary costs of production: feed and labor. The results show why farms are struggling.

From 2005 to 2020, milk sales income per 100 pounds of milk produced ranged from $11.54 to $29.80, with an average price of $18.57. For that same period, the total costs to produce 100 pounds of milk ranged from $11.27 to $43.88, with an average cost of $25.80.

On average, that meant a single cow that produced 24,000 pounds of milk brought in about $4,457. Yet, it cost $6,192 to produce that milk, meaning a loss for the dairy farmer.

More efficient farms are able to reduce their costs of production by improving cow health, reproductive performance and feed-to-milk conversion ratios. Larger farms or groups of farmers – cooperatives such as Dairy Farmers of America – may also be able to take advantage of forward contracting on grain and future milk prices. Investments in precision technologies such as robotic milking systems, rotary parlors and wearable health and reproductive technologies can help reduce labor costs across farms.

Regardless of size, surviving in the dairy industry takes passion, dedication and careful business management.

Some regions have had greater losses than others, which largely ties back to how farmers are paid, meaning the classes of milk, and the rising costs of production in their area. There are some insurance and hedging programs that can help farmers offset high costs of production or unexpected drops in price. If farmers take advantage of them, data shows they can functions as a safety net, but they don’t fix the underlying problem of costs exceeding income.

Passing the torch to future farmers

Why do some dairy farmers still persist, despite low milk prices and high costs of production?

For many farmers, the answer is because it is a family business and a part of their heritage. Ninety-seven percent of U.S. dairy farms are family owned and operated.

Some have grown large to survive. For many others, transitioning to the next generation is a major hurdle.

The average age of all farmers in the 2022 Census of Agriculture was 58.1. Only 9% were considered “young farmers,” age 34 or younger. These trends are also reflected in the dairy world. Yet, only 53% of all producers said they were actively engaged in estate or succession planning, meaning they had at least identified a successor.

How to help family dairy farms thrive

In theory, buying more dairy would drive up the market value of those products and influence the price producers receive for their milk. Society has actually done that. Dairy consumption has never been higher. But the way people consume dairy has changed.

Americans eat a lot, and I mean a lot, of cheese. We also consume a good amount of ice cream, yogurt and butter, but not as much milk as we used to.

Does this mean the U.S. should change the way milk is priced? Maybe.

The FMMO is currently undergoing reform, which may help stem the tide of dairy farmers exiting. The reform focuses on being more reflective of modern cows’ ability to produce greater fat and protein amounts; updating the cost support processors receive for cheese, butter, nonfat dry milk and dried whey; and updating the way Class 1 is valued, among other changes. In theory, these changes would put milk pricing in line with the cost of production across the country.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is also providing support for four DairyBusinessInnovationInitiatives to help dairy farmers find ways to keep their operations going for future generations through grants, research support and technical assistance.

Another way to boost local dairies is to buy directly from a farmer. Value-added or farmstead dairy operations that make and sell milk and products such as cheese straight to customers have been growing. These operations come with financial risks for the farmer, however. Being responsible for milking, processing and marketing your milk takes the already big job of milk production and adds two more jobs on top of it. And customers have to be financially able to pay a higher price for the product and be willing to travel to get it.

Elizabeth Eckelkamp receives funding from United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Marketing Systems and USDA - The National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Authors: Elizabeth Eckelkamp, Associate Professor of Animal Science and Dairy Extension Specialist, University of Tennessee