Big lithium plans for Imperial Valley, one of California’s poorest regions, raise a bigger question: Who should benefit?

- Written by Manuel Pastor, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

The edge of the Salton Sea, a heavily polluted lake with large geothermal and lithium resources beneath it. Manuel Pastor

The edge of the Salton Sea, a heavily polluted lake with large geothermal and lithium resources beneath it. Manuel PastorImperial County consistently ranks among the most economically distressed places in California. Its Salton Sea, the state’s biggest and most toxic lake, is an environmental disaster. And the region’s politics have been dominated by a conservative white elite, despite its supermajority Latino population.

The county also happens to be sitting on enough lithium to produce nearly 400 million batteries, sufficient to completely revamp the American auto fleet to electric propulsion. Even better, that lithium could be extracted in a way consistent with broader goals to reduce pollution.

The traditional ways to extract lithium involve either hard rock mining, which generates lots of waste, or large evaporation ponds, which waste a lot of water. In Imperial Valley, companies are pioneering a third method. They are extracting the mineral from the underground briny water brought up during geothermal energy production and then injecting that briny water back into the ground in a closed loop. It promises to yield the cleanest, greenest lithium on the planet.

The hope of a clean energy future has excited investors and public officials so much that the area is being rechristened as “Lithium Valley.”

In a region desperate for jobs and income, the prospect of a “white gold rush” is appealing. Public officials have been working to roll out the red carpet for big investors, including trying to create a clear plan for infrastructure and a quicker permitting process. To get community groups’ support, they are playing up the potential for jobs, including company commitments to hire local workers.

But Imperial Valley residents who have been on the butt end of get-rich schemes around water and real estate in the past are worried that their political leaders may be giving away the store. As we explore in our new book, “Charging Forward: Lithium Valley, Electric Vehicles and a Just Future,” the U.S. has an opportunity to ensure that these residents directly benefit from the lithium extraction boom, which is an important part of the global shift to clean energy.

Possibilities and perils in ‘Lithium Valley’

Imperial Valley is emblematic of the potential and the risks that have long faced impoverished communities in resource-rich regions.

To understand the possibilities and perils in Imperial Valley, it’s useful to remember that the world is not just moving away from fossil fuel extraction but toward more mineral extraction. Today’s battery technology – necessary for electric vehicles and energy storage – relies on minerals including cobalt, magnesium, nickel and graphite. And mineral extraction is often accompanied by obscured environmental risks.

A prototype for CTR’s lithium-producing geothermal facility, in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Imperial Valley.Manuel Pastor

A prototype for CTR’s lithium-producing geothermal facility, in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Imperial Valley.Manuel PastorIn Imperial Valley, environmental and community organizations are worried about lithium extraction’s water use, waste and air pollution as production steps up and truck traffic increases. When your region’s childhood asthma rate is already more than twice the national average, and dust from the drying lake is toxic, kicking up a “little extra dust” is a big deal.

Comite Civico del Valle, a long-established environmental justice organization in Imperial Valley, has sued to slow down a streamlined permitting process for Controlled Thermal Resources, a company planning lithium extraction there. The group’s concern is that inadequate environmental reviews could result in harm to residents’ health. Both the company and public officials are warning that the lawsuit could stop the lithium boom before it begins.

Local communities are also concerned about how much benefit they will see while the industry profits. They note that the electric vehicle boom driving lithium demand occurred precisely because of public policy. Tesla, for example, has benefited from multiple rounds of state and federal zero-emissions vehicle incentives, including the sale of emissions credits that accounted for 85% of Tesla’s gross margin in 2009 and rose to US$1.8 billion a year by 2023.

Behind these policies and financial incentives have been public will and taxpayer money.

Young advocates with the Imperial Valley Equity & Justice Coalition have been spreading their concerns through the community.Chris Benner

Young advocates with the Imperial Valley Equity & Justice Coalition have been spreading their concerns through the community.Chris BennerWe believe that local residents, not just companies, deserve a return. Rather than promising to just pay for community “benefits,” such as environmental mitigation, contributions to municipal coffers or jobs, the companies could pay “dividends” directly to local residents and communities.

There are models of this dividend approach. For example, the Alaska Permanent Fund gives an annual amount to all residents of that state from revenues obtained from the oil beneath the ground.

In Imperial Valley, the actual ownership of the lithium is complex, involving a mix of privately owned subsurface rights, public lease rights obtained by companies and public rights held by the regional water district to whom companies will pay royalties.

Given the ownership complexities and the desire to benefit as development takes place, local authorities and community organizations persuaded the state in 2022 to pass a per-metric-ton lithium tax to address local needs.

Controlled Thermal Resources CEO Rod Colwell, right, walks near the Salton Sea with a colleague.AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez

Controlled Thermal Resources CEO Rod Colwell, right, walks near the Salton Sea with a colleague.AP Photo/Marcio Jose SanchezThat “flat tax” was bitterly resisted by some in the emerging industry on the grounds that it could make Imperial Valley’s less-polluting extraction method too costly to compete with environmentally damaging imports; after the vote, CTR’s CEO called the legislators “clowns.” Meanwhile, CTR has also agreed to hire union workers in the construction phase. Everyone – companies, communities and government officials – is struggling to balance economic viability with accountability.

Lessons for a just transition

The hesitance of low-income Imperial Valley residents to immediately buy into the lithium vision is deeply rooted in history.

Decades of racial exclusion, patronizing practices and broken promises have led to deep distrust of outsiders who assert that things will be better this time.

Irrigation at the turn of the last century was supposed to bring an agriculture boom, but the early result was a broken canal that released enough water over nearly two years of disrepair to create what is now the Salton Sea. The Salton Sea was then supposed to fuel recreational tourism, but the failure to replenish it with anything but agricultural runoff helped to kill fish, birds and recreation. A more recent scheme to attract solar farms in recent decades delivered little employment and more worries about agricultural displacement.

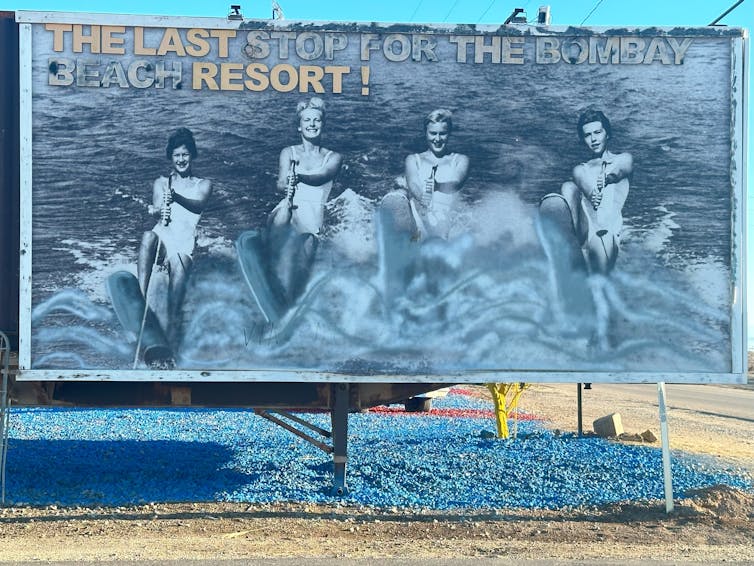

You can still find old billboards promising a resort life on the Salton Sea, which today is one of the state’s most polluted lakes. Wind kicks up toxic dust when the water is low.Manuel Pastor

You can still find old billboards promising a resort life on the Salton Sea, which today is one of the state’s most polluted lakes. Wind kicks up toxic dust when the water is low.Manuel PastorBuilding the supply chain here, too

In recent years, some people have pinned their hopes on lithium. The main site so far in Imperial Valley has been CTR’s Hell’s Kitchen. It’s a fitting moniker on summer days when temperatures regularly exceed 110 degrees.

Ensuring that the surrounding communities benefit from this new lithium boom will require thinking about how to attract not just companies extracting the lithium but also those that will use it. So far, Imperial County has had limited success in attracting related industries. In 2023, a company named Statevolt said it would build a “gigafactory” there to assemble batteries. However, the company’s previous efforts – Britishvolt in the United Kingdom and Italvot in Italy – have stalled without any volts being produced. Imperial County will need serious suitors to make a go of it.

A potentially promising future for modern transportation and energy storage may be brewing in Imperial Valley. But getting to a brighter future for everyone will require remembering a lesson from the past: that community investments tend to be hard-won. We believe that ensuring everyone benefits long term is essential for achieving a more inclusive and sustainable future.

Research for the book from which this article draws was supported by the James Irvine Foundation, New Energy Nexus, the California Wellness Foundation, and Open Society Foundations. Manuel Pastor was also supported by a Residency at the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Center.

Research for the book from which this article draws was supported by the James Irvine Foundation, New Energy Nexus, the California Wellness Foundation, and Open Society Foundations. Chris Benner was also supported by a Residency at the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Center.

Authors: Manuel Pastor, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences