When presidents would send handwritten lists of their nominees to the Senate, things were a lot different

- Written by Peter Kastor, Professor of History & American Culture Studies, Associate Vice Dean of Research, Washington University in St. Louis

President George Washington, left, and his Cabinet: Henry Knox, secretary of war; Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the Treasury; Thomas Jefferson, secretary of state; and Edmund Randolph, attorney general. Currier and Ives/Bettmann - Getty Images

President George Washington, left, and his Cabinet: Henry Knox, secretary of war; Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the Treasury; Thomas Jefferson, secretary of state; and Edmund Randolph, attorney general. Currier and Ives/Bettmann - Getty ImagesThe new U.S. Senate is getting down to business, and one of its first tasks will be to consider Donald Trump’s nominations to federal office.

Trump himself has suggested his preference for recess appointments for Cabinet members. This would avoid the traditional confirmation hearings in the Senate, which are increasingly polarizing, drawn out and partisan.

Discussions of the nominations have included many references to the founders and the process they supposedly devised for confirming nominees.

Yet the founders, in fact, had very little to say on the subject. The Constitution states that the president “by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.”

That’s it. The Federalist Papers, the editorials and pamphlets arguing in favor of ratification that so many students read in high school and college, didn’t add much else on the topic of federal appointments. And the founders did not explore the subject in detail in their own correspondence.

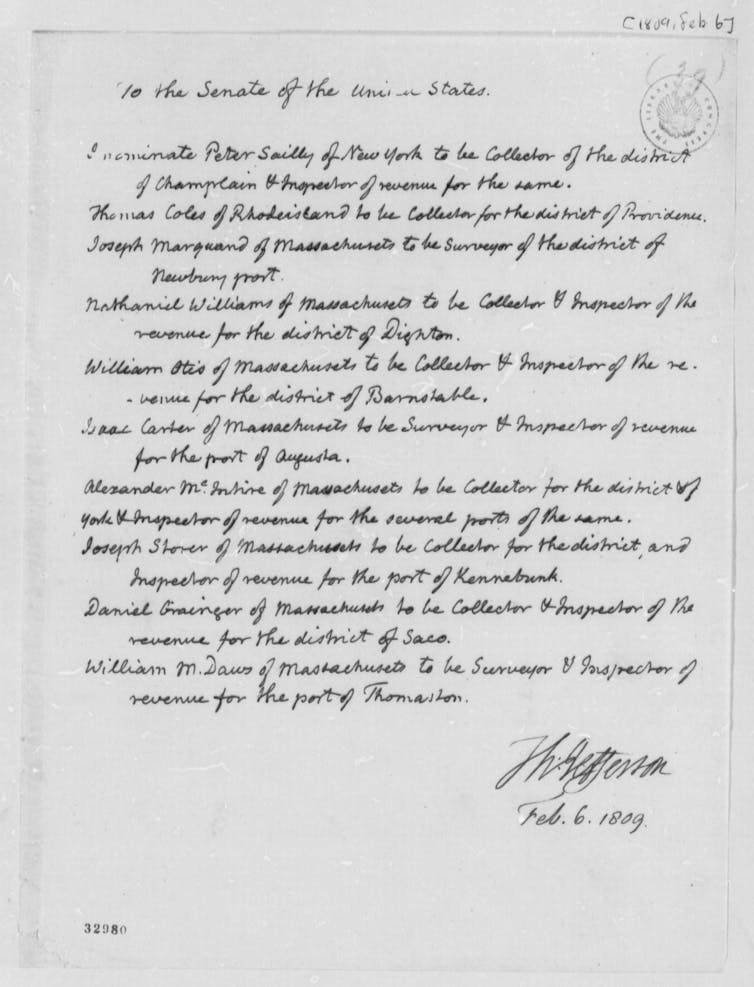

A list of nominations that Thomas Jefferson sent to the Senate on Feb. 6, 1809, including one nominating Joseph Storer of Massachusetts to be ‘Collector of the district, and Inspector of the revenue for the port of Kennebunk.’The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress

A list of nominations that Thomas Jefferson sent to the Senate on Feb. 6, 1809, including one nominating Joseph Storer of Massachusetts to be ‘Collector of the district, and Inspector of the revenue for the port of Kennebunk.’The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of CongressCrucial Senate function

I am a historian who has spent nearly two decades exploring the federal appointment process. I recently launched Creating a Federal Government, 1789-1829, a major digital project that reconstructs the federal government during its first decades.

The Senate considered more than 5,000 nominations to federal civil office from 1789-1829, and I’ve combed through the correspondence of the early federal administrations to understand their approach to this crucial Senate function.

The first presidents were adamant that the confirmation processes should be public and transparent, with Senate oversight. The early Senate was keen to preserve its power over appointments but afforded the president broad discretion in building the executive branch.

What this meant was that “advice and consent” was not decreed as a set of formal rules. Rather, advice and consent took form in practice and emerged from the day-to-day needs of government.

The founders’ model: Transparent inefficiency

George Washington, the first president of the United States, operated from the assumption that the president and the Senate should be actively involved in approving even the lowest-level officials.

After early nominations for the likes of Thomas Jefferson, the first secretary of state, and Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the Treasury, Washington personally nominated hundreds of customs collectors, low-ranking officers in the military and territorial officials. One of the first of these came on Aug. 3, 1789, when Washington dispatched the names of 139 nominees for “Collectors, Naval Officers and Surveyors for the Ports.”

There was barely a federal office that Washington did not think the Senate should consider. His only exceptions were clerks, postmasters and enlisted personnel in the military.

The Senate itself was smaller back then, ranging from 22 members from 11 states when Washington was inaugurated in 1789 to 48 members from 24 states when John Quincy Adams left office in 1829. There were no hearings, nor much in the way of formal vetting. Rather, the Senate discussed nominations among themselves, often voting the same day.

Recess appointments rare

This collaborative system was designed to exemplify checks and balances. But it was also an inefficient one that consumed the president’s and senators’ time and energy.

The process was especially busy at the start of a congressional term, and the Senate Executive Journal – the only detailed account of early Senate proceedings – shows barely a week went by without considering nominations.

Washington’s successors likewise dispatched thousands of names to the Senate on lists often written in their own hand. The Senate responded by devoting much of its daily agenda to considering these nominees.

And the results tell a story: Just as presidents believed that the Senate must be involved with building the federal workforce, senators apparently believed that presidents should have broad discretion. They confirmed over 90% of the nominations they received from 1789-1829, according to my analysis.

This remained the case even during the first period of divided government from 1801 to 1802. The Federalist majority in the Senate consistently approved President Jefferson’s nominations, even though he was from the opposing Republican Party.

Jefferson initially saw considerable partisan advantage to federal appointments. In 1801-1802, for example, he removed 146 customs officials he believed were Federalists and eagerly sought Republicans to take their place. But Jefferson also kept on numerous officials appointed by his Federalist predecessors because he valued their competence – and institutional stability.

From the 1790s through the 1820s, these early presidents rarely used recess appointments, my research shows. When they did, it was primarily to fill vacancies created by death or resignation, after which they quickly submitted formal nominations once the Senate returned.

The modern model: A divided system

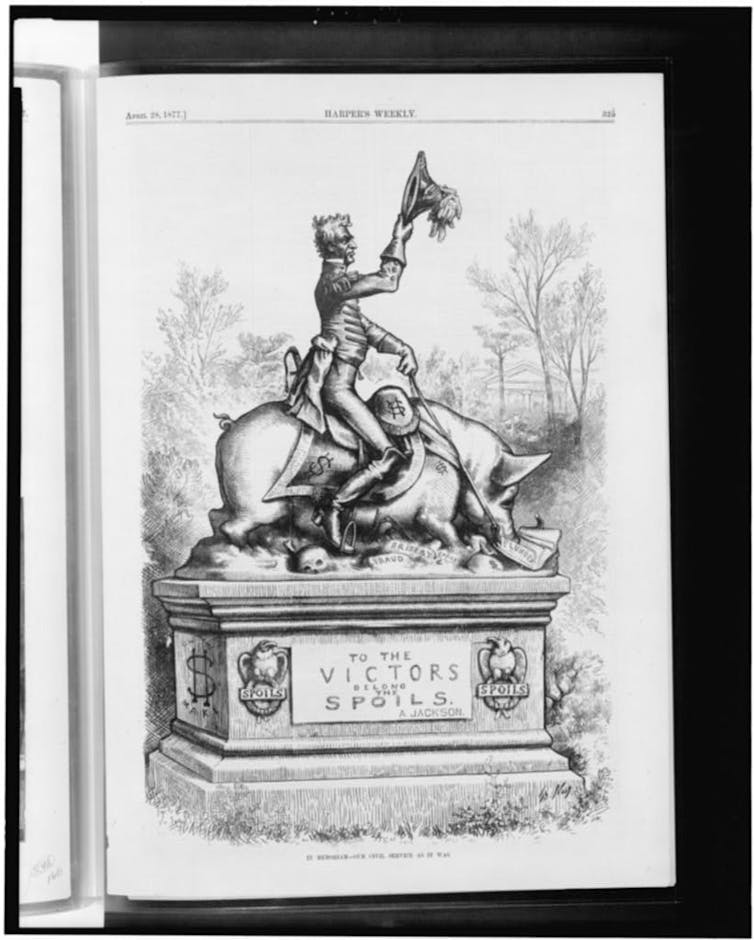

A political cartoon from 1877 showing a statue of Andrew Jackson sitting on a hog atop a tomb, engraved with ‘To the victors belong the spoils − A. Jackson.’Thomas Nast, Harpers Weekly/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A political cartoon from 1877 showing a statue of Andrew Jackson sitting on a hog atop a tomb, engraved with ‘To the victors belong the spoils − A. Jackson.’Thomas Nast, Harpers Weekly/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionThe U.S. began shifting from this relatively constructive give-and-take among the founders in the late 1820s.

When Andrew Jackson came into office in 1829, he proclaimed that to the victor go the spoils, and that included appointments. He treated appointments as a reward for political allies, no matter their qualifications.

Jacksonian patronage became the target for progressive reformers in the late 19th century. They claimed that the spoils system produced a federal system that hired unqualified employees and rewarded political allies rather than serving the general public. They believed civil service reform would produce an effective, efficient and nonpartisan federal government.

Those reforms, combined with a growing federal government that contained too many offices for the Senate to consider, laid the groundwork for today’s structure in which Senate confirmation is reserved for higher-level offices, most of which change with each presidential administration.

Vast majority still approved

Former U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard campaigns with Donald Trump on Oct. 22, 2024, in Greensboro, N.C. Trump has chosen Gabbard as his director of national intelligence.Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Former U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard campaigns with Donald Trump on Oct. 22, 2024, in Greensboro, N.C. Trump has chosen Gabbard as his director of national intelligence.Anna Moneymaker/Getty ImagesReserving advice and consent to high-level positions has shifted the focus of the Senate and the attention of the public entirely to high-value offices and nominees with greater political experience.

Broadcasting confirmation hearings, a practice that began in the 1980s, has only increased the sense that they’ve become political theater. It has made the process more transparent but also created greater opportunities for all involved to convert hearings into political grandstanding.

Yet for all those recent developments, the vast majority of nominations are nevertheless approved. This is especially true for non-Cabinet and lower-level posts.

For positions such as U.S. attorney, assistant secretary of state or director of the Bureau of Land Management, presidents usually submit nominations to the Senate when the Senate is in session. The Senate in turn usually confirms with spirited discussion but limited opposition.

All presidents have made use of temporary appointments, and some nominations generate major public controversies, but they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

And the process of nominating people for those offices remains a remarkable link to the earliest years of the republic.

The rules, however, are changing.

The first Trump administration used temporary appointments far more often than his predecessors. And he may do the same in his second term.

Meanwhile, Republicans in the Senate faced criticism for dragging their feet on nominations to important civil and military offices during the Obama and Biden administrations.

These recent developments constituted breaks from long-standing practices and profound breaks from how the Founding Fathers imagined the process of advice and consent.

This story is part of a series of profiles explaining Cabinet and high-level administration positions.

Peter Kastor receives funding from ACLS and NEH. Grants from these organizations contributed to Creating a Federal Government.

Authors: Peter Kastor, Professor of History & American Culture Studies, Associate Vice Dean of Research, Washington University in St. Louis