How the oil industry and growing political divides turned climate change into a partisan issue

- Written by Joe Árvai, Director of the Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability | Professor of Psychology, Biological Sciences, and Environmental Studies, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Donald Trump's pro-fossil fuel positions stand in sharp contrast with efforts to protect the climate.Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Donald Trump's pro-fossil fuel positions stand in sharp contrast with efforts to protect the climate.Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty ImagesAfter four years of U.S. progress on efforts to deal with climate change under Joe Biden, Donald Trump’s return to the White House is swiftly swinging the pendulum in the opposite direction.

On his first day back, Trump declared a national energy emergency, directing agencies to use any emergency powers available to boost oil and gas production, despite U.S. oil and gas production already being near record highs and leading the world. He revoked Biden’s orders that had withdrawn large areas of the Arctic and the U.S. coasts from oil and natural gas leasing. Among several other executive orders targeting Biden’s pro-climate policies, Trump also began the process of pulling the U.S. out of the international Paris climate agreement – a repeat of a move he made in 2017, which Biden reversed.

None of Trump’s moves to sideline climate change as an important domestic and foreign policy issue should come as a surprise.

During his first term as president, 2017-2021, Trump repealed the Obama-era Clean Power Plan for reducing power plant emissions, falsely claimed that wind turbines cause cancer, and promised to “end the war on coal” and boost the highly polluting energy source. He once declared that climate change was a hoax perpetuated by China.

Since being elected again in November, Trump has again chosen Cabinet members who support the fossil fuel industry.

But it’s important to remember that while Donald Trump is singing from the Republican Party songbook when it comes to climate change, the music was written long before he came along.

Money, lies and lobbying

In 1979, the scientific consensus that climate change posed a significant threat to the environment, the economy and society as we had come to appreciate them began to emerge.

The Ad Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate, commissioned by the U.S. National Research Council’s climate research board, concluded then that if carbon dioxide continued to accumulate in the atmosphere, there was “no reason to doubt that climate changes will result.” Since then, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by about 25%, and temperatures have risen with it.

The report also concluded that land use changes and the burning of fossil fuels, both of which could be subject to regulation, were behind climate change and that a “wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late.”

But none of this came as a surprise to the oil industry. Working behind the scenes since the 1950s, researchers working for companies such as Exxon, Shell and Chevron had made their leaders well aware that the widespread use of their product was already causing climate change. And coinciding with the Ad Hoc Study Group’s work in the late 1970s, oil companies started making large donations to national and state-level candidates and politicians they viewed as friendly to the interests of the industry.

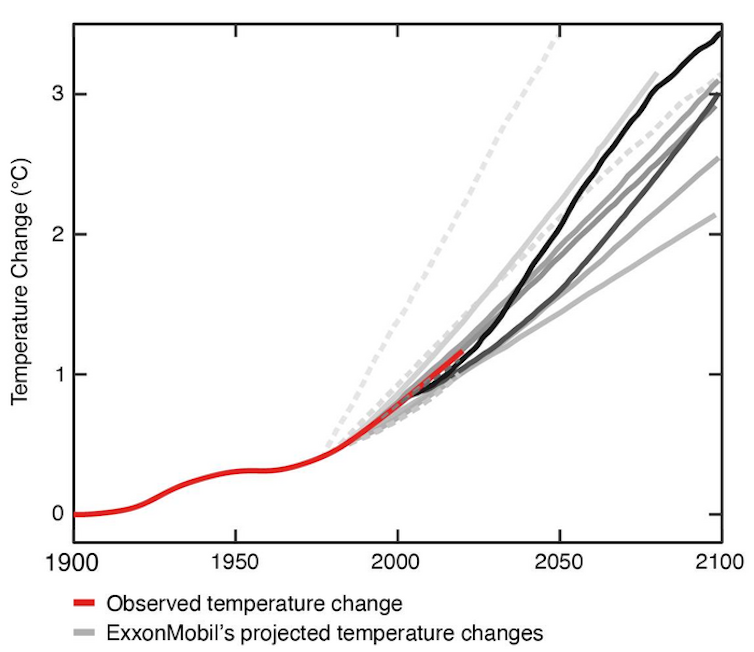

A summary of all global warming projections reported by ExxonMobil scientists in internal documents and peer-reviewed publications, 1977 to 2003, superimposed on observed temperature change (red). Solid gray lines indicate global warming projections modeled by ExxonMobil scientists; dashed gray lines are projections shared by ExxonMobil scientists from other sources. Shades of gray reflect start dates: earliest (1977) is lightest; latest (2003) is darkest.Geoffrey Supran

A summary of all global warming projections reported by ExxonMobil scientists in internal documents and peer-reviewed publications, 1977 to 2003, superimposed on observed temperature change (red). Solid gray lines indicate global warming projections modeled by ExxonMobil scientists; dashed gray lines are projections shared by ExxonMobil scientists from other sources. Shades of gray reflect start dates: earliest (1977) is lightest; latest (2003) is darkest.Geoffrey SupranThe oil industry also implemented a disinformation campaign designed to cast doubt about climate science and, in many cases, about their own internal research. The strategy, ripped from the pages of the tobacco industry playbook, involved “emphasizing uncertainty” to cast doubt on the science and calling for “balanced” science to sow confusion.

This strategy was helped by the creation and financial backing of lobbying organizations such as the Competitive Enterprise Institute and the Global Climate Coalition, both of which played central roles in spreading falsehoods and casting doubt on the scientific consensus about climate change.

By 1997, when 84 countries signed the Kyoto Protocol to curb global greenhouse gas emissions, the oil industry had built an effective apparatus for actively discrediting climate science and opposing policies and actions that could help slow climate change. So even though President Bill Clinton signed the treaty in 1998, the United States Congress refused to ratify it.

Partisan politics and the psychology of belonging

The Kyoto Protocol experience demonstrated that the lobbying and disinformation tactics used by oil companies to discredit climate science could, on their own, be highly effective. But they alone didn’t shift climate change from a scientific question to an issue of partisan politics. Two additional ingredients for completing the transition were still absent.

The first of these came during the election campaign of 2000. At the time, the coverage of the major news networks converged on dividing the country into red states, which lean right, and blue states, which lean left.

This shift, though seemingly innocuous at the time, made politics even less about individual issues and more like a team sport.

Rather than asking people to construct their voting preferences based on a wide range of issues – from abortion and gun rights to immigration and climate change – votes could be earned by reminding and reinforcing for voters which team they should be cheering for: Republicans or Democrats.

This shift also made it easier for the fossil fuel industry to keep climate change off state and federal policy agendas. Oil companies could focus their money, lobbying and disinformation on Republican-controlled states and swing states where it would make the biggest difference. It shouldn’t surprise anyone, for example, that it was a red state senator, James Inhofe of Oklahoma, who brought a snowball to the Senate floor in February 2015 to “prove” that the planet was not warming.

Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma brings a snowball to the Senate in February 2015. Every year since then has been warmer than 2014, with 2024 the warmest on record.The final ingredient had everything to do with human nature. Building on the analogy of a rivalry in sports, the red vs. blue state dynamic tapped into the psychological and social forces that shape our sense of belonging and identity.

Subtle but powerful social pressures within groups can make it harder for people to accept ideas, evidence and arguments from those outside the group. Likewise, these within-group pressures lead to preferential treatment for members who are in alignment with the group’s perspectives, up to and including placing greater trust in those who appear to represent the group’s collective interests.

Within-group pressures also create stronger feelings of belonging among those who conform to the group’s internal norms, such as which political positions to support. In turn, stronger feelings of belonging serve to further reinforce the norms.

Where to from here?

Opposing or supporting action on climate change has become part of millions of Americans’ cultural identity.

However, doubling down on climate policies that are in lockstep with our own political leanings will serve only to strengthen the divide.

A more effective solution would be to set aside political differences and invest in building coalitions across the political spectrum. That starts by focusing on shared values, such as keeping children healthy and communities safe. In the wake of devastating fires in my own city, Los Angeles, these shared values have risen to the top of the local political agenda regardless of who my neighbors and I voted for. It’s clear to all of us that the consequences of climate change are very much in the here and now.

Natural disasters across the U.S. have also brought the risks of climate change home for many people across the country. This, in turn, has led to bipartisan action on climate change at the local and regional levels, and between government and the private sector.

The U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of 24 governors from both parties who are working to advance efforts to slow climate change, is one such example. Another example is the many U.S. companies with ties to government that participate in the First Movers Coalition, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industries that have proven difficult to decarbonize, such as steel, transportation and shipping.

But, unfortunately for climate action, examples like these are still an exception rather than the norm. And this is a problem because the current climate challenge is much bigger than a single city, state or even country. The past year, 2024, was the hottest on record. Many parts of the world experienced extreme heat waves and storms.

However, every movement has to start somewhere. Continuing to chip away at the partisan barriers that separate Americans on climate change will require even more coalition building that sets an example by being ambitious, productive and visible.

With the new Trump administration poised to target the recent progress made on climate change while preparing executive actions that will increase greenhouse gas emissions, there’s no better time for this work than the present.

Joe Árvai has received funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, and NASA. He is currently a member of the U.S. EPA's Chartered Science Advisory Board, and a member of the National Academies Board on Atmospheric Science and Climate. He can be found on Bluesky at @decisionlab.bsky.social, and on Instagram at @joearvai.

Authors: Joe Árvai, Director of the Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability | Professor of Psychology, Biological Sciences, and Environmental Studies, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences