Recession will hit job-poor parts of Western Sydney very hard

- Written by Phillip O'Neill, Director, Centre for Western Sydney, Western Sydney University

This is the second of three articles based on newly released research on the impacts of a lack of local jobs on the rapidly growing Western Sydney region.

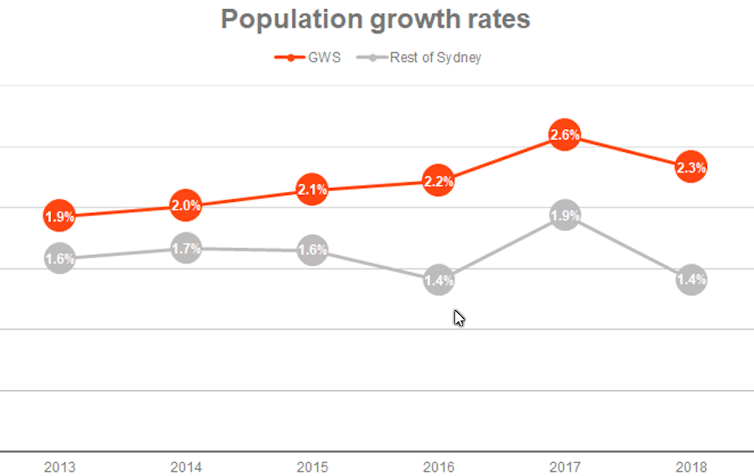

After 2016 – but before COVID-19, it should be said – Western Sydney experienced a mini jobs boom. Growth came from the region’s extraordinary surge in population, driven by record levels of immigration.

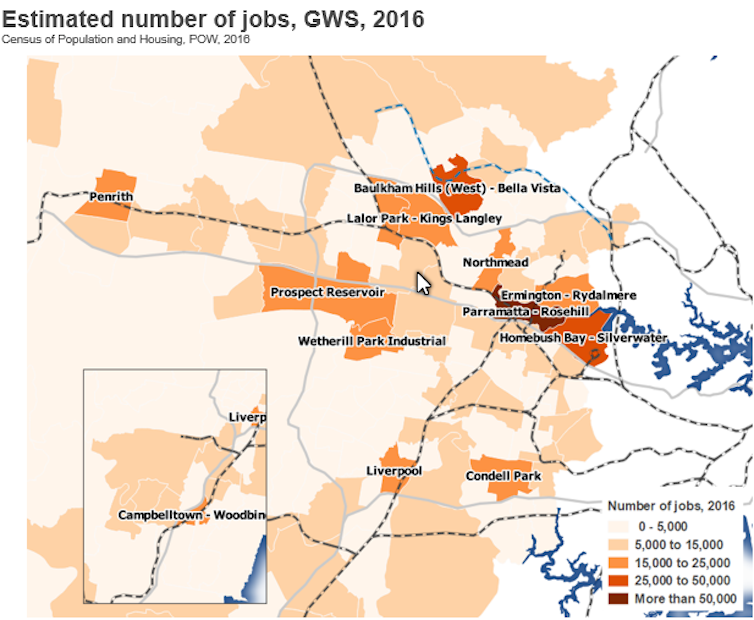

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

The residential construction sector was flat-out. Also thriving were the population-serving sectors: health care and social assistance, education and training, retailing, and accommodation and food services.

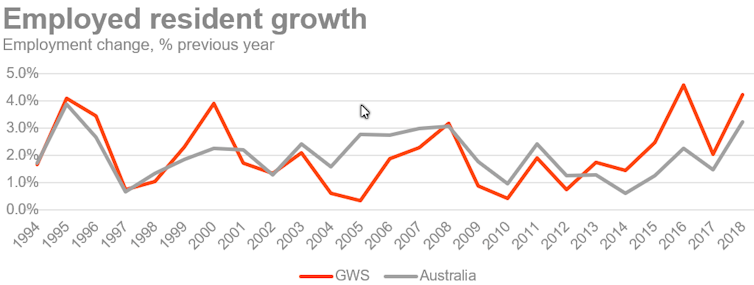

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

The residential construction sector was flat-out. Also thriving were the population-serving sectors: health care and social assistance, education and training, retailing, and accommodation and food services.

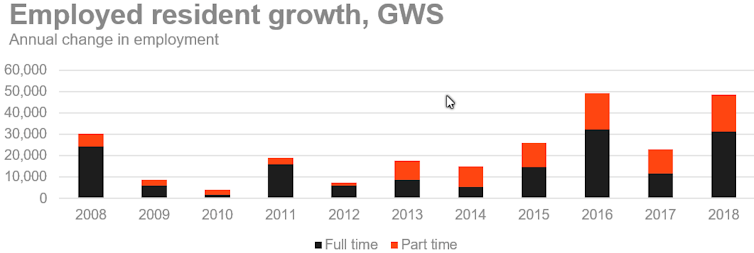

Centre for Western Sydney, Data: National Economics (NIEIR), 2018, Author provided

Read more:

Jobs deficit drives army of daily commuters out of Western Sydney

But the tide has turned

By late 2019 the construction boom had ended, as it always does. Now, with a COVID-19 recession, the capacity of the population-serving sectors to maintain jobs, let alone stimulate job growth, is greatly reduced.

The mini jobs boom was good for Western Sydney’s long-suffering unskilled workers. Construction, for men, and for women the population-serving sectors – retailing and the domesticated side of the health, personal and child-care sectors – offered jobs without qualifications hurdles.

Centre for Western Sydney, Data: National Economics (NIEIR), 2018, Author provided

Read more:

Jobs deficit drives army of daily commuters out of Western Sydney

But the tide has turned

By late 2019 the construction boom had ended, as it always does. Now, with a COVID-19 recession, the capacity of the population-serving sectors to maintain jobs, let alone stimulate job growth, is greatly reduced.

The mini jobs boom was good for Western Sydney’s long-suffering unskilled workers. Construction, for men, and for women the population-serving sectors – retailing and the domesticated side of the health, personal and child-care sectors – offered jobs without qualifications hurdles.

Centre for Western Sydney, Data: National Economics (NIEIR), 2018, Author provided

Now it’s back to insecure, short-term work stints in a dwindling pool of jobs. Often these are outside the regulated labour market, always needing a car, and competing with many others looking for the same work.

The COVID-19 recession, like the early 1990s recession, will hit those Western Sydney neighbourhoods with large concentrations of unskilled workers as hard as anywhere else in Australia.

Read more:

The economy in 7 graphs. How a tightening of wallets pushed Australia into recession

Even in the boom, local jobs were scarce

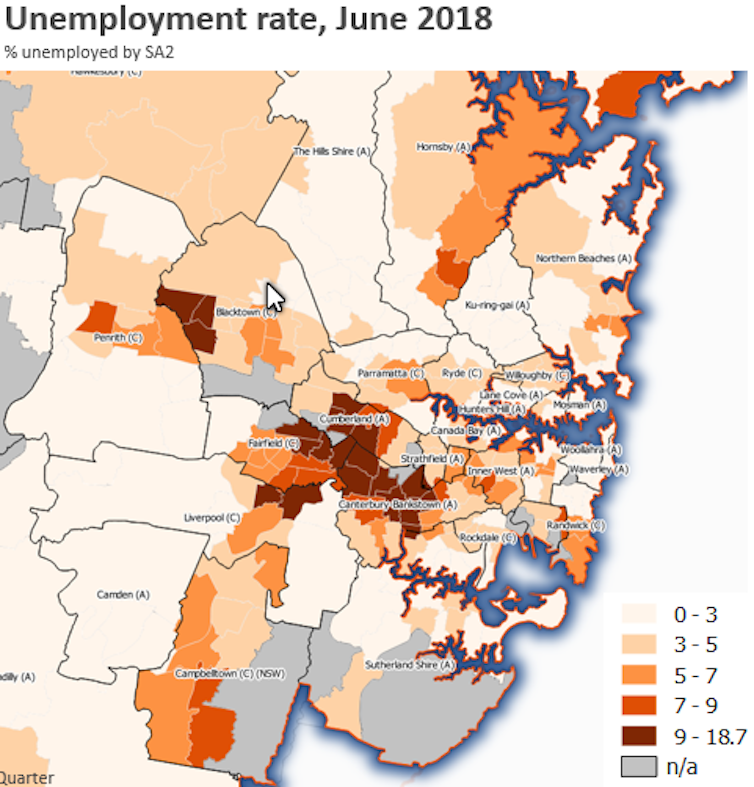

Even before this recession, indeed at the height of Western Sydney’s 2016-18 jobs boom, employment access for these neighbourhoods was miserable. Using the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) community-level statistical area, SA2, we find unemployment rates in 2018 were double and triple the metropolitan average.

Centre for Western Sydney, Data: National Economics (NIEIR), 2018, Author provided

Now it’s back to insecure, short-term work stints in a dwindling pool of jobs. Often these are outside the regulated labour market, always needing a car, and competing with many others looking for the same work.

The COVID-19 recession, like the early 1990s recession, will hit those Western Sydney neighbourhoods with large concentrations of unskilled workers as hard as anywhere else in Australia.

Read more:

The economy in 7 graphs. How a tightening of wallets pushed Australia into recession

Even in the boom, local jobs were scarce

Even before this recession, indeed at the height of Western Sydney’s 2016-18 jobs boom, employment access for these neighbourhoods was miserable. Using the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) community-level statistical area, SA2, we find unemployment rates in 2018 were double and triple the metropolitan average.

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

In the Fairfield area, Fairfield City SA2 had 18.7% unemployment in 2018, Fairfield-East 16.0% and Fairfield-West 12.2%. In the Blacktown area, Bidwell-Hebersham-Emerton had 16.3% unemployment, Lethbridge Park-Tregear 12.9% and Mount Druitt-Whalan 11.3%. In the Cumberland local government area, Guilford-South Granville had 14.7% and Guilford West-Merrylands West 10.8%. In Liverpool, Ashcroft-Busby-Miller had 14.8% unemployment.

Western Sydney’s jobs deficit is having broad and unacceptable consequences. Significant numbers of households record no paid work for long periods of time. Unemployment in the 15-24 age group typically exceeds 25%.

About the same proportion of this age bracket has completely dropped out of education and the workforce, as our recent report on youth unemployment in Western Sydney explains.

These areas have among the highest levels of socio-economic disadvantage in Australia. Joblessness has become inter-generational. It’s a result of poor education and training qualifications, patchy job experience, immobility, too many others seeking the same jobs, round and round.

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

In the Fairfield area, Fairfield City SA2 had 18.7% unemployment in 2018, Fairfield-East 16.0% and Fairfield-West 12.2%. In the Blacktown area, Bidwell-Hebersham-Emerton had 16.3% unemployment, Lethbridge Park-Tregear 12.9% and Mount Druitt-Whalan 11.3%. In the Cumberland local government area, Guilford-South Granville had 14.7% and Guilford West-Merrylands West 10.8%. In Liverpool, Ashcroft-Busby-Miller had 14.8% unemployment.

Western Sydney’s jobs deficit is having broad and unacceptable consequences. Significant numbers of households record no paid work for long periods of time. Unemployment in the 15-24 age group typically exceeds 25%.

About the same proportion of this age bracket has completely dropped out of education and the workforce, as our recent report on youth unemployment in Western Sydney explains.

These areas have among the highest levels of socio-economic disadvantage in Australia. Joblessness has become inter-generational. It’s a result of poor education and training qualifications, patchy job experience, immobility, too many others seeking the same jobs, round and round.

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

Read more:

A closer look at jobless youth in Western Sydney points us to the solutions

Women are excluded from work

Away from the job-starved neighbourhoods, poor access to jobs strikes at Western Sydney households in relatively hidden ways, but we can see it in low rates of labour force participation.

For Australia, at the 2016 census, the male participation rate was 64.8% while the female rate was 8.9 points lower at 55.9%.

In outer Western Sydney, in the greenfields mortgage belt, participation rates are significantly higher than national averages. In Camden local government area, for example, the rate in 2016 was 70.1% while The Hills recorded 68.0%. These rates indicate young dual-income households are prepared to move to the outer suburbs for affordable housing, in exchange for the long commute.

In the old industrial districts of Western Sydney, however, participation rates are five or more percentage points below the national average. We see extremely low rates of female participation in three areas: Cumberland at 47.9%, Canterbury-Bankstown 47.7% and Fairfield with an extraordinarily low 43.2%. These rates compare poorly with female participation rates elsewhere in Sydney, such as Inner West at 65.5%, North Sydney 67.6%, Waverley 63.6% and Sutherland 61.5%. The difference in rates is arresting.

Disadvantage flows through generations

The obvious consequence of lower labour force participation is lower household income. Longer term, households with lower participation rates are likely to have lower retirement incomes. And the children in households where fewer adults are working tend to have impaired development and poor job prospects.

We can see, therefore, Western Sydney’s jobs deficit can crush a neighbourhood, packing it with intense, persistent poverty. It can also make things very tough in households scattered across other suburbs. Poor access to jobs reduces workforce participation, especially among women, for all sorts of reasons, but with outcomes not compatible with the idea of Sydney as the generous, wealth-generating Emerald City.

In a region that has a million workers but only 790,000 jobs, many workers migrate daily to other regions to find work. Others with less competitive CVs miss out completely. The consequences are grossly unfair. The COVID-19 recession will only make them worse.

The Centre for Western Sydney has released three reports on Western Sydney’s growing jobs deficit. You can read the reports here.

Centre for Western Sydney, Author provided

Read more:

A closer look at jobless youth in Western Sydney points us to the solutions

Women are excluded from work

Away from the job-starved neighbourhoods, poor access to jobs strikes at Western Sydney households in relatively hidden ways, but we can see it in low rates of labour force participation.

For Australia, at the 2016 census, the male participation rate was 64.8% while the female rate was 8.9 points lower at 55.9%.

In outer Western Sydney, in the greenfields mortgage belt, participation rates are significantly higher than national averages. In Camden local government area, for example, the rate in 2016 was 70.1% while The Hills recorded 68.0%. These rates indicate young dual-income households are prepared to move to the outer suburbs for affordable housing, in exchange for the long commute.

In the old industrial districts of Western Sydney, however, participation rates are five or more percentage points below the national average. We see extremely low rates of female participation in three areas: Cumberland at 47.9%, Canterbury-Bankstown 47.7% and Fairfield with an extraordinarily low 43.2%. These rates compare poorly with female participation rates elsewhere in Sydney, such as Inner West at 65.5%, North Sydney 67.6%, Waverley 63.6% and Sutherland 61.5%. The difference in rates is arresting.

Disadvantage flows through generations

The obvious consequence of lower labour force participation is lower household income. Longer term, households with lower participation rates are likely to have lower retirement incomes. And the children in households where fewer adults are working tend to have impaired development and poor job prospects.

We can see, therefore, Western Sydney’s jobs deficit can crush a neighbourhood, packing it with intense, persistent poverty. It can also make things very tough in households scattered across other suburbs. Poor access to jobs reduces workforce participation, especially among women, for all sorts of reasons, but with outcomes not compatible with the idea of Sydney as the generous, wealth-generating Emerald City.

In a region that has a million workers but only 790,000 jobs, many workers migrate daily to other regions to find work. Others with less competitive CVs miss out completely. The consequences are grossly unfair. The COVID-19 recession will only make them worse.

The Centre for Western Sydney has released three reports on Western Sydney’s growing jobs deficit. You can read the reports here.

Read more https://theconversation.com/recession-will-hit-job-poor-parts-of-western-sydney-very-hard-139385